Introduction

The past 40 years have seen a huge growth in the volume of research on small business and entrepreneurship in the United States (US), United Kingdom (UK), and Europe (Blackburn and Kovalainen 2009). While entrepreneurship is very much its own subject, for the purposes of this paper, the term small business research is used to encompass entrepreneurship as well as the more mainstream small entity-based research. While the emphasis of small business research varies between jurisdictions, there is a strong academic community that aims to provide greater insight about the functioning of small businesses and the specific nature of entrepreneurship, involve students in experiential small business consulting projects, and directly assist regulators in decisions about modifying the regulatory framework for such entities. As Blackburn and Koivalainen (2009) identify, small business research is clearly an area where educationalists, practitioners, academics, and policy makers all come together, since the field provides low conceptual barriers to entry. However, one of the consequences of this is that some small business research can be too ‘customer-focused’, adopting poor methodological approaches, and failing to acknowledge the more mainstream academic literature. While there is a perceived need to raise the overall quality of small business research (Perren, Berry, and Blackburn 2001), it is a young and vibrant area, with vast potential for growth and improvement.

Clearly then, small business research offers abundant unexplored opportunities for scholars and practitioners alike. Practical, yet scholarly research can provide owners models of how to approach many of the specific problems they regularly encounter as part of owning a Small to Medium-sized Enterprise (SME). This type of research is more typically published in specific small business-related academic journals, and within the US, two such outlets are provided by the Small Business Institute® (SBI). The SBI is the premier US organization that engages business, education, and the community, and publishes the Small Business Institute Journal (SBIJ) and the Journal of Small Business Strategy.

The Small Business Institute Journal offers an outlet for researching small business for academics, while also serving as a resource for SME owners and practitioners. In sum, the Journal has the primary purpose of “publishing scholarly research articles and cases in the fields of small business management, entrepreneurship, and field based learning” (“Small Business Institute Journal” 2021). The breadth of topics in the SBIJ is therefore wide and providing the state of research on a multitude of topics and the nature of research published benefits universities and small businesses alike. While the Journal of Small Business Strategy is also an applied research journal, it has a narrower focus by specializing in articles with a significant strategy orientation oriented toward a small business/entrepreneurship educator and small business consultant. To date, both journals have a long and successful history in publishing seminal small business and entrepreneurial research, but what is overdue is a systematic literature review of each journal’s contents to identify research trends and potential gaps for future work. This paper provides such a literature review, but has chosen to focus on the SBIJ, due to its more practical and case-based orientation, that, in theory, should serve as a better basis for identifying the array of small business research areas and topics that have been researched by US academics and practitioners during the period 2008-19.

Considering that the SBI celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2022, this paper’s review of the 106 papers published in SBIJ journal from its inception in 2008 to 2019 is a timely reminder of the contribution that SBI’s membership plays in raising awareness about the issues facing US small businesses, and helping to forge links between businesses, educational establishments and the community. The purpose of this paper is twofold: (1) provide trends and patterns of the paper types published in SBIJ and (2) identify potential research gaps. For the first objective, this review sought to classify papers by type, methodologies used, index papers for researchers, educators, and practitioners, and exhibit various trends of research published in the Journal. For the second objective, constructing trends and patterns of papers published resulted in identifying gaps within the journal. This yielded new potential areas of research, including types of research, to be considered.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: (1) explaining the methodology employed for the review of SBIJ, the “Journal”; (2) describing the findings of the review including proposed future research topics and methodologies; (3) identifying new areas for research; and (4) offering concluding remarks about the literature review and identifying how it might be expanded.

Journal review methodology

A systematic approach using qualitative data analysis methods was used to achieve the objectives outlined above. The review process was a three-stage process (with multiple iterations per stage) to attain data saturation resulting in subject domains, paper topics, and trends of published papers. Data saturation results when many recurring themes, subjects or concepts emerge from the iterative cycles of analyzing qualitative data.

First stage: review of articles

The initial review of the Journal consisted of ascertaining the range of topics covered by the published papers. For the first stage, attribute coding was applied to attain basic information about the papers in the Journal. In essence, attribute coding lists basic descriptive information about a data set, in this case, the papers published in the Journal (Krippendorff 2013; Saldana 2016). The results of attribute coding provided the essential structure by which each paper was assigned generic attributes. Examples of attributes are year, volume, number, title, author(s), and initial categories of the paper type and subject. Starting with an attribute coding method also provided for establishing an early data set in Excel for future classification and initial indexing for later coding methods.

After attaining the essential attributes to catalog the articles, descriptive coding was used to identify and initially label the subject of focus for each article. Descriptive coding is used to summarize, using one word, what a passage in a qualitative data set is about (Saldana 2016). For this first stage, the title and abstract of the paper were used to provide initial categories of subjects for each article. By focusing on the title and abstract basic subject areas were tagged a general classification. This phase of the review also resulted in an initial classification of paper type as being either research or conceptual.

A wide range of diverse topics resulted from a first iteration of the review. The task of categorizing by concept became increasingly challenging during phase one since some of the categories did not neatly fit within a traditional realm of research topics as found in standard academic journals that have a narrow scope of topics. In more than a few cases, some papers did not neatly fit within a general subject area. A second iteration to classify article topics was accomplished with the aim of identifying all possible subject areas with the intent of narrowing the list during the second stage of review.

Second stage: review of papers

For the second stage of the review, descriptive coding was also applied for refining phase one subjects identified for each paper. For the second stage, descriptive coding was applied by examining the title, abstract, paper purpose (or introduction) and conclusion. By reading the paper’s abstract, purpose/introduction and conclusion, key descriptors were gleaned that yielded a wider yet improved schema of categorization for the papers. Descriptive coding also resulted in reassigning articles initially placed in a category into a new or different category.

After this process, concept coding was used to narrow the number of topics. Concept coding is used to assign a macro meaning to a data set (Saldana 2016, 2015). As the results yielded a very wide array of topics from the papers, these were ‘mapped’ within a more macro-framework. This led to the creation of a two-level macro classification, where content areas were first classified into a ‘Domain’, and then, partly due to the diversity of content within each domain, allocated a specific descriptive sub-category coding called a ‘Topic’.

In addition to establishing Domains and Topics, the paper re-examined article type identification from stage one. The types of articles expanded from research and conceptual to include pedagogical research. Categorizing the articles as research, conceptual, and pedagogical was a recurring challenge in the review process such that the refining process persisted throughout all three phases. As will be discussed below, the paper type categories expanded during phase three of the review.

Third stage: review of articles

The goals for stage three of the review were to refine the Domains and corresponding Topics; identify data types; identify data collection or data/information sources; and identify the paper’s methodology. Reading through the purpose, methodology, results, and discussion encompassed the third stage of the process. This phase also served to expand the number of paper types published in the journal.

Structural coding was applied for the third phase of the review. It is used to gather topic lists or indexes of major categories (Krippendorff 2013; Saldana 2016; Schreier 2012). Structural coding is useful as it provides lists of topics and indexing categories, which highlights repetitive identifications and minimally identified categories (Saldana 2016). As such, it is appropriate for listing data types found in the papers, ways of collecting data, methodology, and expanding types of papers identified (e.g. research versus conceptual or pedagogical). The finalized structuring from Domain to Topics resulted in identifying gaps and future areas of research.

Findings from the review of SBIJ papers 2008-19

Article domains and topics

The review of papers published in the Journal yielded the following general observations:

-

Several topics exhibit a defining characteristic of the Journal by entertaining a diversity of SME topics of which are specific issues SME’s confront.

-

Relatively underrepresented subject areas included debt financing, CSR/Sustainability, organizational structure, organizational behavior, state policy, law and legislative risks, gender and ethnic diversity, and business closure.

-

High concentration of papers on strategic management, small business consulting, small business and education, and entrepreneurial behavior.

-

Research methodology emphasized regression analysis and descriptive statistics (i.e. percentage response, percentage of totals).

-

Qualitative studies exhibited diverse qualitative methods of data collection, data types, analysis, and interpretation.

After analysis via the three stages of coding, the 106 papers published in SBIJ during 2008-2019 were each classified into the research “domains” and “topics” shown in Table 1. Unsurprisingly, due to the nature of small business research, the papers were extremely diverse in terms of their chosen domain and topics. The issues that small businesses must confront are highly specific and emerge from various factors the entity must address before progressing on to a new or different stage of operation. In other words, small and medium sized enterprise (SME) issues are not generalizable under broad topics that may define academic journal niches (Parry 2015). In contrast, SMEs face immediate issues needing immediate attention before using limited resources (i.e. cash) and therefore be able to continue for another year or meet needed growth targets that supply cash for the next operating year. Another explanation to the diversity of topics is that faculty are curious and seek to cover areas of interest of which relate to small businesses. Alternatively, researchers may encounter a small business (as client, professional connection, etc.) facing specific issues and commence learning, researching, or working through the problem with the SME. In sum, the array of topics published are both diverse and specific. Most importantly, SMEs are complex; face a multitude of issues; and highly effective in meeting customer requirements or decipher customer markets all while under a degree of uncertainty about cash flows (Jarvis et al. 2000).

Research domains and publication concentrations

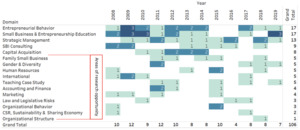

Concentrations in certain domains and topics remained constant during 2008-2019. Figure 1 illustrates the proportion of papers by domain with sections separated by Underrepresented (under 4% of total papers); Mid-Section (under 9%) and Concentrations (12-16%). Both the underrepresented and mid-section articles account for thirteen domains. The concentrations include only three Domains.

While this “high level” overview of the domains is useful, the next section of this paper attempts to explain why the “underrepresented” and “mid-section” research domains are under-researched and identify possibilities for future work in these areas.

Analysis of the “underrepresented” and “mid-section” domains

While this section of the paper discusses the underrepresented and mid-section domains covered in SBIJ, it must be acknowledged that some of the ‘gaps’ identified may be covered by papers published in JSBS, the SBI’s sister journal. The headings in italics provide and identify future research topics.

Accounting and finance research

One of the problems facing the small-business researcher is that small business and certain business-related subject areas, such as accounting and finance, are typically seen as separate fields of study, with the small business regarded as unfruitful environment for meaningful research (Parry 2015). Although certain aspects of small business research will be the same internationally, the respective prevalence of certain kinds of research is obviously jurisdictionally dependent due to data availability and differences in the regulatory framework for such entities. For instance, as all types of privately held limited liability entities in the UK and Europe must publicly file financial statements and prepare financial statements for their members, it is much easier to study issues related to small business financial reporting, disclosure, and auditing (Minnis and Shroff 2017) However, despite this. what was relatively surprising was the lack of SBIJ publications that directly investigated the relationship between state or federal policy and small business success. Similarly, there is a need for more comparative analysis of each US State’s policy or regulatory framework for promoting and supporting entrepreneurship and small business activity, such as the impact of sales and use tax and the overall reporting burdens placed on such entities. Other more controversial unexplored areas include issues related to ethics and fraud, and whether small business owners install the necessary internal controls to prevent inappropriate behavior by employees.

Changes in accounting and finance research

Accounting and finance functions have changed in the last decade and will continue to do so given the disruptive characteristics of Big Data, data analytics, and AI (Warren, Moffitt, and Byrnes 2015; Vasarhelyi, Kogan, and Tuttle 2015). More importantly, though, is the qualities of change impacting SME accounting functions and purpose. As such, research design in this area should not focus on established methods used in large firm research that are survey based using deductive approaches to test general propositions (Parry 2015). Rather, it may be that a mix of quantitative and qualitative approaches are more suitable for the complexly intertwined element of SMEs, owners, and customers (Jarvis et al. 2000).

SME accounting firm research

SME accounting firms can no longer rely on basic services of audits, compiling financial statements or completion of taxes. They need to pursue consulting and insight about what financial and non-financial information means for the future for current and potential clients. They need to understand how the decisions made by owners produce the opportunities and/or constraints the owners must deal with. Specifically, they must first understand the owner’s understanding of accounting information before being able to advise them (Parry 2015). The challenge and therefor future research opportunities lies in how SMEs can implement data analytics and specifically how SMEs implement Big Data applications (Coleman et al. 2016; Schneider et al. 2015). Future research opportunities exist in working with and examining how SMEs adapt to technology disruptions impacting accounting and small accounting firms.

Data analytics research on SMEs

If a SME maintains financial ledgers, they have data. If they have product distribution, the have data. If they have access to public census data, they have data. If they provide services to customers, they have data in memos, emails, meetings, and consulting recommendations. In sum, it is not necessarily the technology that is central to leveraging “big” data but rather an entity’s ability to see the possibilities of mining what they have and how it is related to daily and future operations (Muller and Jensen 2017). Evaluating various data forms, financial and non-financial, will increasingly become an expanded advisory role for SME accounting firms to serve small business (Carey 2015). Technology platforms are readily available via accounting software, Excel, Power BI, and Tableau. This is in part the new role of accounting and the above may be facilitated by SME accounting firms (Carey 2015). Indeed, the research into SMEs expands out to SME accounting firms attempting to adapt to a rapidly changing environment.

Law and legislative risks

As mentioned above, law and legislative risks at the municipal and regional level have varied effects on SMEs particularly in area of risk management. Additionally, information made public and what remains non-public with respect to public information (sales taxes, revenues, etc.) as well as municipal regulations of which hinder or boost SME business opportunities can vary from state to state. Research in these areas, while unique to municipalities, states or regions can still reveal useful findings associated with best practices in dealing with new legislation of which impacts SME operations. For instance, Heriot et al. (2010) offer an exploratory study on the impacts of minimum wage increases and health care tax. A follow up to their explorations could examine case studies of how SMEs are currently addressing health care issues, costs and the potential of ever more changes in legislation. Additionally, examination of how increases in minimum wage impacts SMEs either through improved employee morale, short-term effects, and long-term costs effect the business. The legalization of marijuana offers an irregular avenue of research on how consulting service in accounting, marketing or operations address the associated risks of working with such a client (Stringham et al. 2017). Alternatively, Stringham et al. (2017) provide a commentary by which further research could examine employee accommodation and drug testing issues. A deep study of select SMEs could examine the concreate actions or improvised actions owners take in navigating this change in the employment landscape.

Marketing research

Marketing is the communication of value proposition to existing and potential customers. To be sure, some of the articles in the Strategic Management Domain incorporate marketing as part of the whole study or commentary. Yet, marketing as a specific Domain offers much in research opportunities. The relevant study of buying Groupon deals offers many possibilities for future study with SMEs (Broekemier, Chau, and Seshadri 2011). The authors provide recommendations drawn from the results of the study of which may be avenues of future research. For example, in attempts to gain repeat customers from Groupon deals, the SME should promote those products/services that are frequent revenue generators versus infrequently purchased products/services. Research of an SME or a group of SMEs offers the perspective of the how and why of returns, success, failures, and future promotions through Groupon deals.

Debt financing and capital structure research

In terms of other unexplored areas, research in debt financing could encompass case study methodologies across different SME industries or a few SMEs each representing a case (Yin 1994). A case study methodology could examine the barriers many SMEs face attempting to acquire debt to finance both operations and long-term asset investments. Relatedly, examining the strategies used by SMEs in attaining debt and the practices of being able to pay back debt quickly would be areas of interest to SMEs. While statistical data exists on debt financing of small business, (Merkovich 2019) the diversity of reasons why and how certain businesses attain and can pay debt are missing.

A case study approach that reveals differences among a set of SMEs regarding successful or unsuccessful debt financing and repayment approaches would benefit researchers and practitioners. The research by Hendon and Bell (2011) provides results from exploring gender differences and debt financing for small business. Their discussion provides avenues by which case studies could be employed to further investigate the reasons for differences besides those discussed (e.g. risk factors, financial structure, goals of having a small business) or further examine those areas identified.

Organizational structure research

Another area for future research is that of organizational structure. Organizational structure is tightly related to an entity’s strategy and resources (Mintzberg 1998; Chandler 1972; Martin and Eisenhardt 2000). As such, the gap in organizational studies articles should prompt researchers to creatively examine the nature, dynamics, and resilience (or lack thereof) of SME organization structures and behavior. Qualitative research and action research are methods (Reason and Bradbury 2002) that would contribute to this area of study for SMEs since large quantitative data sets may be unavailable. Because large populations (employee size) are generally unavailable for most SMEs with less than 75 employees, qualitative research offers potential rich findings that would be informative to both academics and practitioners. The conceptual paper on entrepreneurial behavior by Nandram and Samso (2008) offers future investigations into a few entrepreneurs’ behaviors with respect to their search and taking opportunities in the context of sustainability. Each entrepreneur would be a distinct case resulting in comparing distinct behaviors and tendencies in their approach to business. Carland and Carland (2009) offer varied perspectives in their examination of the entrepreneur and innovation. As such, which of those perspectives play out in part or in whole with entrepreneurs? In addition, how does the organization begin to form based on the entrepreneur’s behavior towards innovation? Research into these areas may also uncover idiosyncratic structures highly connected to the owners, even as the entity continues to grow.

CSR and sustainability research

The area of CSR, Sustainability, integrated reporting, conscious capitalism, and the Sharing economy has been overlooked. While CSR and sustainability have at least 2 decades long history in research, it has limited examination in the Journal. Firstly, SMEs have multiple metrics of performance and do not solely focus on profitability (Jarvis et al. 2000). Second, certain SMEs begin with a vision that equally includes financial value and social value. Specifically, SMEs may form to make a profit and have a social impact yet struggle with the tension between the two (Pirson 2012) while also pursing international objectives (Mesa and Usrey 2014). Research into why entities, particularly SMEs, become certified as B Corps is an avenue of research that could contribute to this area of SMEs (Harjoto, Laksmana, and Yang 2018). Alternatively, added research as to the practices of B Corps and their impact provides SMEs perspectives on the benefits of B Corp status versus sustainable practices absent the certification (Sharma, Beveridge, and Haigh 2018).

Success v. failure of startups

A review of the literature on small business closure found that most studies focus on the factors associated with the ‘success’ or ‘failure’ of small businesses, with a tendency to associate business closure with failure (Stokes and Blackburn 2001). As many entrepreneurs start up entities and then move on to other businesses, it would be interesting to study their mindsets, and also identify why businesses close rather than fail (Blackburn and Kovalainen 2009).

Gender and diversity research

Lastly, while gender diversity has been the subject for several papers in SBIJ, this topic alongside ethnic diversity and social inclusion are badly underrepresented topics from both a small business and entrepreneurship perspective (Ahl 2006; Smallbone, Kitching, and Athayde 2010). The difficulties that certain ethic groups have in starting small businesses and raising finance require exploration, as does the present level of diversity within small business boardrooms and the role played by non-executive directors within growing family-run businesses. In addition, the links between ethnic diversity, competitiveness, and entrepreneurship needs further analysis.

Analysis of the “concentrated” domains

While the previous section identified the research domains that are relatively unexplored in SBIJ, this section briefly focuses on the “concentrated” domains found at the bottom of Figure 1. The three concentrated domains of Strategic Management, Small Business & Entrepreneurship Education, and Entrepreneurial Behavior represent 44.3% of all papers published in SBIJ during 2008-19, and the paper provides four perspectives as to why they represent such a dominant research domain in the Journal. First, strategic initiatives, entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial behavior are frequently researched as they are driven by SME needs. Second, the research is favored because strategy and entrepreneurial behavior are favored domains in the context of business. A third view may be in part driven by the SBI priority of supporting university business education by focusing on small businesses and their needs. The unique opportunities for experiential learning are abundant and offer students ways of learning that traditional modes of teaching cannot provide. The three concentrated domains offer rich “live” case studies for students to learn via unstructured information and in the context of business uncertainties (Hoffman et al. 2016). Fourth, there may be a lack of interest in conducting field research on SMEs in the underrepresented areas.

Paper trends in SBIJ by year of publication

To this point, the paper has merely focused on the total number of papers published in each topic and domain during the period 2008-19. While this is indicative of the popularity of each domain and helps to identify potential gaps in the literature, it does not allow the identification of research trends within the pages of the Journal.

The followingan summarizes the above discussion by illustrating the trends of published papers by year. Figure 2 illustrates the yearly number of papers published in each identified domain. The top quarter of Figure 2 illustrates the concentrated areas of research. The lower three-quarters of the map illustrates a diversity of topics intermittently published. The irregularity and sparseness of publications starting from “Family Small Business” and ending with “Organizational Structure” offers opportunities for research as discussed above.

Paper types, data sources, and research methodology

While analyzing papers by research domain is an important part of identifying research trends and areas of need, it can be a relatively crude method of classifying papers. Within each domain, there are clearly various types of paper, with each using different methodologies and data collection methods. The next section of the paper analyses the 106 published papers by paper type and the data sources and methodologies used, and by doing so, provides suggestions for new approaches in applying data and methodology in future research.

Paper types

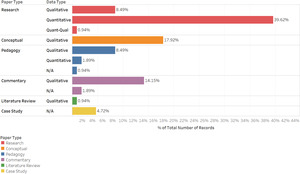

Approximately 50% of the papers published in the Journal are research articles, with the remainder being commentary, conceptual papers, pedagogy papers or teaching case studies:

-

Research Papers examine phenomenon through the collection, analysis, evaluation and interpretation of quantitative data, qualitative data, or both.

-

Conceptual Papers develop propositions and/or expand on theories. Models are developed and/or new perspectives are proposed towards understanding SME issues.

-

Pedagogy Papers generally encompass a discussion on the importance of pedagogy and its relationship to working with SMEs.

-

Commentary Papers provide accounts of personal experience; provide perspectives on SME topics; and/or heighten awareness of SME issues.

-

Literature Reviews provide a general survey of the literature, including academic and/or practitioner literature, on a topic.

-

Case Study papers are educational resources developed and made available through the Journal to business educators.

Data Types

Research papers in the journal primarily used quantitative rather than qualitative data, with four of the five other paper types favoring the use of a qualitative approach to research.

Data collection methods and data sources used

Figure 4 exhibits the various forms of data sources and collection used within the Journal. The variety of quantitative and qualitative data sources used suggests the creativity of researchers in finding readily available data sources for small business research. While surveys afford researchers a wide distribution of available and willing participants, some being convenient participants such as students, researchers have also found data sources available outside of administering a survey.

The mode of collecting data and type of data collected should obviously be related to the purpose of the paper and its research questions (Yin 1994; Hair et al. 2006). As Figure 4 illustrates, quantitative data was mainly collected via survey. Significant uses of surveys seeks data that measures an individual’s scale of preference one time and provides numerous data points facilitating correlation, causation, and various probable distributions via calculated means (Hair et al. 2006). Aggregated quantitative data, however, provides a narrow frame of meaning since owner behaviors, business environments, industry structures, operational qualities, and other factors are the complex context of any SME (Saldana 2015; Yin 1994).

Qualitative data was the primary data type used for conceptual papers and for a small portion of research papers. Much of the “qualitative” data is split between interviews and literature sources. Coding the data type for qualitative data for this review, however, was challenging. For many conceptual and commentary papers, qualitative data included practitioner/researcher’s experience (recollection), publicly available documents, internal curriculum, non-scholarly literature and some scholarly literature. Thus, “literature” encompassed much of the previous list unless “documents” (government, I.R.C, legal documents) were a large part of the data.

Obviously, conceptual papers should draw from the literature in developing theory and/or propositions for research. However, some conceptual and commentary papers used qualitative data using literature sources, web sites, and documents specific to the paper. While all of these sources are viable qualitative data, coding methodology was absent, which will be discussed later in this paper.

Research papers using quantitative data through survey, for example, have examined the relationship between universities and small businesses (Young 2009); how managers use accounting reports (Shields and Shelleman 2011); and gender and ethnic differences in entrepreneurs (Hendnon and Bell 2011). The studies represent examples from the Journal that use quantitative data by which greater understanding on small business can stimulate further quantitative and qualitative data studies. Such studies, however, need not be replications. Rather they should further investigate the richer meanings of the statistical findings of which the Journal serves as a type of “library”. The studies could further develop the data collection tools previously used to focus on certain questions. Alternatively, the findings of each paper could stimulate a case study by which interviews, field data and business documents serve to enrich the meaning of the statistical outcomes of the study.

Conceptual papers are supported by qualitative data. Figure 4 indicates “literature” as a primary source of developing models, SME strategy concepts, ideas for theory and other conceptual elements designed to stimulate further investigation by researchers or as applications for practitioners. The term “literature” however encompasses an eclectic type of which is not primarily academic literature. Examples of using academic literature and professional journals in forming conceptual papers is found in Liesz and Maranville (2008) in their examination of ratio analysis. Fang et al. (2010) also provide an example of drawing from the academic literature in examining family business differences through the lens of institutional theory. Their conceptual model and propositions developed could be further examined completely or in part through large sets of participants (quantitative data) or via qualitative data collection methods (interviews, field studies). Indeed, a further study on their findings could examine the differences of how SMEs behave relative to institutional theory, which is typically associated with larger entity research.

Additional examples of conceptual paper types providing future research opportunities is found in Herio, et al. (2012). They provide future research questions into examining the use of entrepreneurs to teach in small business courses in light of AACSB boundaries and frameworks. Their descriptive application yielding future research questions offer an array of various quantitative and qualitative data driven studies which would benefit universities and ultimately benefit students and small business. Williams and Aaron (2008) re-examine specialization in light of small businesses resulting in a series of propositions opening up opportunities for a variety of quantitative or qualitative driven studies. These are only a few examples of how the Journal has published conceptual papers of which provide future research and application opportunities for academics and students.

Commentary papers offer a diversity of views, descriptive accounts of experience, and descriptive applications of interest to SMEs. The hidden gems found in commentary papers is that while they provide descriptions or applications of practical issues for SMEs, they quietly or explicitly solicit further research. For example, Cook et al. (2012) discuss community development and involvement by students when engaging in experiential SBI projects. The paper indirectly prompts examining how the university and small businesses relationship may change. This is a similar theme as found in Sonfield (2008) on the success of SBI consulting with small businesses.

Commentary papers primarily rely on internal sources of data support: experience, general source documents as found in curriculum programs, or practitioner journals. The data supporting commentary papers should include more external documentation rather than internal. (e.g. an entity’s own curriculum as a basis for a paper, or a bias to focusing only on experience versus the experience of others supported by academic or practitioner journal citations). The aim is not to convert commentary papers into research papers. Rather the aim is to support comments and provoke the reader to seek out additional resources for insights given their heightened awareness from reading the paper.

Conceptual and commentary papers are informative for both researcher and practitioner and belong in the repertoire of the Journal given its mission. As such, expanding the types of qualitative data and methodology may be a viable option for researchers. Conceptual papers can be developed through well-documented field observations and entity documents in addition to a sound review of the literature. Pilot studies with SMEs, which can lead to larger future projects, can be used to develop conceptual papers by using observations, limited interviews and a deep analysis of extant literature. As opportunities surface to conduct work and research with SMEs, researchers can seek out data sets such as business physical layout, employee locus of work and control, image based data from the website or other entity sources, field observations, and impromptu inquiries that probe into employee/owner tasks “at the moment”. Combined they provide a rich array of qualitative data for the development of conceptual or commentary papers.

Methodologies Used

Figure 5 illustrates the types of data and method used by the papers in the Journal. The most prevalent methodology used was regression analysis, which parallels the heavier use of quantitative data previously discussed above. Regression analysis the primary quantitative methodology employed although statistically based methods also incorporated factor analysis, discriminate analysis and various tests for integrity of results. A few examples extracted from the review indicate varied uses of regression: measuring small business owners perceptions of financing time frames relative to cash flows (Dunn and Liang 2011); factors associated with owners creating a business plan and capital acquisition (Dearman and Bell 2012); and analysis of organizational behavior characteristics and commitment to remain with the business (Koutroumanis, Alexakis, and Dastoor 2015).

For quantitative studies, descriptive statistics was the second most popular method used. Examples of using descriptive statistics in the Journal’s papers provide a clear set of data variables for comparative purposes as found in Shields and Shelleman’s (2013) study of business cycles and implications of strategic revenue; and Cormier-MacBurnie et al.'s (2018) study of the relationship of Trip Advisor reviews to customer relatedness and entity performance.

The qualitative data papers adequately represented recognized qualitative methodologies. The methods listed in Figure 5 are primarily descriptive terms, derived from the coding process, to help determine how authors used, analyzed and discussed the qualitative data supporting conceptual and commentary type papers. The following is the classifications of qualitative methods used to distinguish how qualitative data was used by each published paper.

-

Comparative Review—this method compares different sources of data either to serve in finding relationships or contrasts relative to the paper’s conceptual or commentary goals.

-

Descriptive Application—used for conceptual, pedagogy and commentary papers where the authors describe how to apply certain tools, laws, or practices to SMEs facing specific issues.

-

Descriptive Account—the authors describe an account of an event or events and use varied sources of qualitative data to support or question the event. The data sources also serve to developing models or applications. This method was also used for conceptual, pedagogy and commentary type papers.

-

Data Themes/Patterns—identifying themes or recurring patterns found in varied data sources to explain or support events, phenomenon, or practices.

These methods fit the goals of research, conceptual, commentary, and pedagogy papers by providing applications, guidance, discuss perspectives, and compare sources of data to describe phenomenon of interest to SMEs.

Conceptual papers that used descriptive accounts and descriptive applications had a wider array of non-traditional “literature” as data sources. The nature of a “descriptive account” paper tends to draw from the author(s)’ wealth of experience from practice, research or both. Descriptive accounts were included as part of conceptual papers as they provide applications resulting from gleaning various “literature” sources. Descriptive accounts used literature sources such as books, websites (e.g. government sites); periodicals and newspapers, professional manuals, legal documents, the internal revenue code, and traditional academic journals.

Other papers using qualitative methodology recognized in the literature are as follows:

-

Critical biography

-

Ethnography

-

Theory/proposition development

-

Case Study

An interesting finding is several papers that were identified as using qualitative data lacked a description of the methodology used. In contrast, research papers based on quantitative data provided a clear methodology of analyzing the data at various iterations. In summary, qualitative data-based papers did not have a clear methodology section whereas quantitative research papers included a methodology section with development stages in the process of analysis.

Qualitative research involves inquiry (Creswell 1998), coding (Saldana 2016), data analysis (Miles and Huberman 1994) and, interpretive results (Alvesson and Karreman 2011). Qualitative data is raw and derived from people’s experiences. Qualitative data is collected from everyday experiences and transactions (Reason and Bradbury 2002) via observation, interviews and documents. As such, it reflects reality and requires deliberate processes of analysis. “With qualitative data one can preserve chronological flow, see precisely which events led to which consequences, and derive fruitful explanations” (Miles and Huberman 1994, 1).

Providing a full review of the benefits of qualitative research is beyond the scope of this paper. However, for small business and entrepreneurial research, established qualitative methods should find fertile ground within SME research yielding a multitude of concepts, models, principles, flexible practices, strategic deployment options, behavioral qualities of owners and other relevant findings. Using rigorous and varied qualitative methods provides greater insight into the data collected. Saldana (2016) provides multiple approaches to analyzing interview data, each of which are useful for specific research projects and other methods that span multiple projects. While quantitative methods provide results framed within a narrow window of validation, qualitative data provides meaning (Saldana 2016). Moreover, rather than conducting research on SMEs or business owners, an approach would be to conduct research with the business through sound Action Research methodology (Reason and Bradbury 2002). Indeed, the notion of conducting research with the business is already a significant part of what the SBI conducts in tandem with promoting the increased use of experiential learning (Hoffman et al. 2016). The missing element by which to derive richer and wider results is through a systematic process of qualitative methodology.

Finally, case study methodology, of which Yin (1994) is frequently cited, is well suited for small business research. Like qualitative methodology, sound case study research should have sound design and mixed data sources of which may be both quantitative and qualitative. If one case study is conducted on an entity, researchers should consider the same case study design for another entity either within the same industry or different industry. In this way, a greater set of results that are relevant to practitioner and researcher alike are available. Moreover, the results may overlap, but more interestingly the results may differ at certain points thereby reflecting the diverse nature of small business operations and entrepreneurs.

Identifying new areas for future small business research

From our analysis of the research domains, paper types, data types, and methodologies found within the pages of SBIJ during 2008-19, there is clear evidence to suggest a need to apply new methodologies in established areas and explore under-researched domains. Aligning with the SBIJ’s objective of providing applied research for SMEs, below are potential avenues for future research that may serve to greatly enhance existing knowledge.

Capturing significant phenomenon: routine business practices and uncommon ways of work

-

Case studies on everyday operations and the significance of the mundane in SMEs

Using different types of SMEs, each representing a case study, to examine certain practices that are overlooked may uncover value contribution unknown or unnecessary tasks. SME practices could fall within any of the underrepresented and/or mid-section domains individually or in combinations. For example, the routine processes in accounting could reveal how the needs stemming from the entity’s changing organization structure may lead to combining capabilities or more cost-effective processes. Related to this area is conducting studies that expand, revisit or have been inspired by the Journal’s conceptual and commentary papers where entrepreneurs reflect on the routines enhance or possibly inhibit entity growth. The discussion on methodologies provides a handful of extant methods that can be applied such as: ethnography, critical biography, and theory development all of which are appropriate to an SME setting. Finally, SME research tends to be driven by an assumption that research methodologies and theories applied to large firms may be scaled down to the small firm (Jarvis et al. 2000). This is akin to scaling down a Mahler symphony to a solo piano composition and assume the same criteria of scoring, performance, sound, and overall impact of the piece will remain the same.

-

Multiple measures of performance

Jarvis et al (2000) provide evidence of SMEs that measure performance outside of profitability. They also point to the idiosyncratic complexities of SMEs individually and as a whole that contribute to measuring performance which is related to both organizational behavior and organizational structure. As such, research into what constitutes performance metrics in SMEs warrants further investigation. Examining multiple measures of performance parallels well with using multiple types of data. What constitutes performance on a weekly basis? What is the relationship to having cash and the possibility of generating future cash (e.g. new customer or client)? These questions align well with action research methods where researchers collaboratively work with SMEs versus the distant investigator researching an entity.

-

Implementing profit sharing in SMEs

Investigating the incentive structure in SMEs, particularly in the growth stage and moving from the entrepreneurial to the bureaucracy stage, would be of both interest and use for SMEs. As entities grow, formalized organization structures expand as do policies and routine procedures. Incentive structures may foster the sustaining of entrepreneurial behavior. The domains of family businesses, organizational structure, organizational behavior and accounting can be integrated in investigating this topic and the feasibility of implementing profit sharing in SMEs.

-

Collaborative efforts and co-opetition between SMEs

Certain industries, such as the craft brewing industry, operate under conditions of co-opetition and collaboration. This may take the form in sharing resources (e.g. long-term assets that are portable) or collaborate by serving in guilds (brewers association guilds, cider guilds, etc.). Examining how these entities compete using modified perspectives of industry structures (suppliers, customers, entrants) would be of interest to SMEs and scholars. Additionally, an analysis of entry and exit by firms within industries or sub-component industries would shed light regarding regions of stability or instability. This would relate directly to capital and debt acquisition topics. The domain of CSR also provides opportunities in how SMEs may share the costs and/or efforts of sustainability efforts through collaborative efforts.

Disruption Topics

-

SME accounting firms in a world big data, analytics and artificial intelligence

While this topic was addressed under the “accounting” domain, it merits additional attention here. The sources of data generated by SMEs can be captured, cleaned and structured towards decision-making. The pressing issue, however, is that SMEs do not have the time to structure and cleanse data—particularly unstructured data. SME accounting firms have historically provided a stable set of auditing, compilation, review, accounting software implementation, and tax services. However, the state of operational performance and financial health in the past required hours of intellectual labor, of which didn’t justify the cost to either SME accounting firm or SME client. An examination of what tasks have historically been accounting labor that can be done through automation, bots, and data cleansing processes opens up new markets to serve SMEs. Research questions should examine new types of services SME accounting firms can provide that are of value to SME clients.

-

Implementing emerging technologies—from basic to advanced levels.

At what stage are SMEs implementing emerging technologies? What is the size of the SME relative to its stage of implementation? What types of SMEs (i.e. business products/services) are implementing disruptive technologies? How are such implementations financed? How do owners view the importance of implementing new technologies? These questions directly relate to the unique nature of SME growth structurally (i.e. organizational structure), the leveraging of limited personnel (e.g. accounting, human resources), and its developing idiosyncratic capabilities that may not fit within conventional strategy research.

-

Capturing, leveraging and using intellectual capital

What are the types of human capital, structural capital and relational/customer capital used in SMEs? How can identifying such capitals be operationalized and made practical to SMEs? What is the relationship between the type of data captured by the SME and its intellectual capital? These questions can guide research on human resource management specific to SMEs with respect to the challenges of talent acquisition.

-

International perspectives

What are the strategies used by SMEs to thrive in markets driven by global forces? What is the nature of SME service, talent acquisition, and customer retention when global markets offer viable substitutes that may overshadow what SMEs offer? What is the structure, performance and/or financial position of SMEs that provide services/products that just cannot be outsourced overseas?

Conclusions

This paper reviewed the articles published in the SBIJ during 2008-2019 to identify trends and patterns amongst the research and explore the gaps in US small business research. The 106 Papers were first coded by domain, topic, type (e.g. research, conceptual), data type used, and methodology used. Published papers were then used to highlight the potential for further research opportunities. Finally, a list of possible future areas was provided with respect to methodologies employed, data sources used, and for topics not currently covered in the journal. While this analysis of existing US small business research should prove useful to a range of stakeholders, it is obviously limited in scope. In order to identify other fertile areas for future research area and improve the overall quality of small business research, there is clearly a need for further structured literature reviews of other small business related journals that compares US small business research with work being conducted internationally. While many of the research domains explored may be similar to those explored in the pages of SBIJ, the prevalence of certain topics and method of study may be very different, which serves to enrich our understanding of both small businesses and the entrepreneurs that run them.