Ever since the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913, which established Congress’s authority to levy income taxes, the United States (U.S.) tax code has steadily become more complex and comprehensive (Cassidy et al., 2024). The current U.S. tax code, if printed, would be approximately 6,871 pages; 75,000 pages if all of the federal tax regulations and official tax guidance are included (Danielle & Danielle, 2022). It comes as no surprise that the average small business owner, even when acting entirely in good faith, will run into issues with their tax filings and payments. These issues can stem from mistakes made by the taxpayer, whether they are a business or individual, their tax preparer, or the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and can often result in substantial civil penalties. The IRS assessed over 50 million civil penalties totaling $84 billion in 2024 (Faulkender et al., 2025). The good news is that following the passage of the Omnibus Taxpayers’ Bill of Rights Act in 1987, there have been efforts to promote more transparency in the IRS’s actions, improve accessibility to due process, and provide resolution options outside of the courtroom (Meland, 1988).

Since there will always be limits on the IRS’s reach, the agency relies on voluntary tax compliance with penalties and enforcement actions focused on deterring willful noncompliance (Morris, 2010). The IRS, in turn, has established guidelines in the Internal Revenue Manual (I.R.M.) allowing for penalty abatement and late elections as a gesture of goodwill to taxpayers who were acting with ordinary care and prudence. Additionally, the IRS has established policies and procedures to help correct errors. While the application of these options is not always uniform (Morris, 2010), policies and procedures are in place, even if the taxpayer is unaware of them. Taxpayers may hire a tax professional, although that option is not always financially feasible for individuals or small businesses.

Small business owners need to gain a fundamental understanding of the IRS issues they may encounter and the available options for resolution. While the first reaction a taxpayer has to an IRS notice might be to panic, there is often information in that notice clarifying the issue and offering at least one option for how the taxpayer can respond. We will first outline some of the common reasons taxpayers do not respond to notices. Tax morale is a concept that provides a foundation for understanding the factors that influence individual compliance behavior. Social and personal norms, as well as institutional factors, contribute to decision-making. Fear or dislike of the IRS and its processes can drive action or inaction.

Through a series of real-world cases, we will highlight several common issues that small business owners can encounter with the IRS and how different policies and procedures helped resolve each issue favorably for the taxpayer. The cases highlighted involve a representative acting on behalf of the small business; however, these are actions that taxpayers can take directly if they trust the process and communicate with the IRS rather than embracing non-pecuniary barriers to compliance. The following literature review discusses the concept of tax morale and the constructs that may explain why a taxpayer may choose not to comply. {See Table 1 for terms and definitions}

Literature Review

Compliance and Tax Morale

The lack of compliance relating to tax law and procedures, in an economic sense, is a problem that affects public policy, law enforcement, organizations, ethics, and possibly all these areas together (Andreoni et al., 1998). Noncompliance can also be intentional or unintentional on the part of the taxpayer (Fischer et al., 1992). A procedural definition of compliance is “the taxpayer files all required tax returns at the proper time, and that the returns accurately report tax liability by the Internal Revenue Code, regulations, and court decisions applicable at the time the return is filed” (Fischer et al., 1992 referencing Roth et al. 1989, pg 2). In this paper, the taxpayer is the small business owner, acting as an individual and making decisions on behalf of the organization. When a small business taxpayer receives a notice from the IRS, their level of compliance with the request can be influenced by psychological and cognitive factors, which are inherent to the individual, and may justify the action or alter their intention to comply (Alm, 2019).

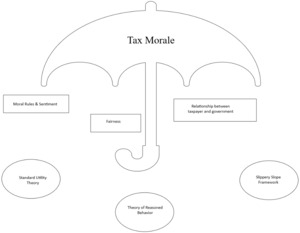

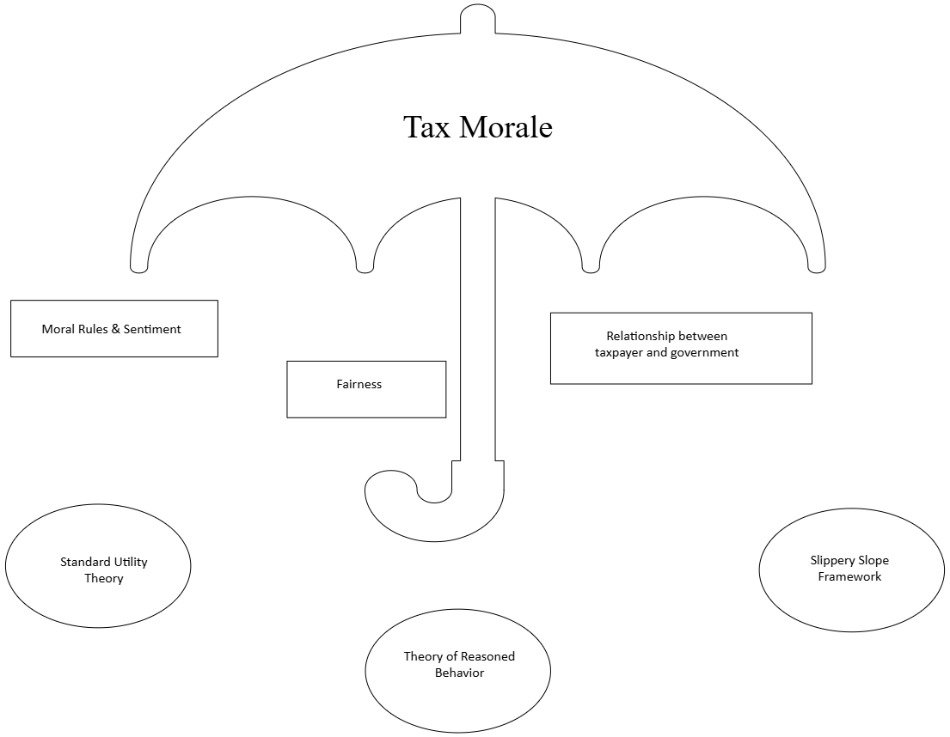

Economists have historically posited that classical standard utility theory drives compliance intention, assuming that individuals are rational and purely self-interested. A rational taxpayer, in this context, will choose the situation that provides the most significant expected utility when the outcome is uncertain (Alm, 2019). Behavioral research has proven that people are not always rational, especially in situations involving risk (Evans & Over, 1997). Tax morale is a complex concept first introduced by researchers from the Cologne School of Tax Psychology in the late 1960s and later evolved into the working theory of tax morale, which is most used by scholars to describe a conglomeration of factors influencing taxpayer compliance (Horodnic, 2018). This concept adopts a holistic approach to taxpayer decision-making, suggesting that social norms, personal values, and institutional perceptions influence a willingness to comply. Taxpayer morale serves as an umbrella, overarching many theories that round out the constructs of taxpayer compliance.

Bobek et al. (2007) found that personal and subjective norms are the most important factors influencing compliance, as one’s morals and the acceptance of peers’ ideology shape compliance judgments. In their study, injunctive norms (reflecting societal expectations) also influenced compliance behavior, but to a lesser extent than personal and subjective norms. Descriptive norms, or what people believe is typical or common behavior, also play a part in taxpayer compliance decisions. However, Bobek et al. (2007) demonstrate that taxpayers’ beliefs outweigh what they perceive others to be doing. The theory of reasoned behavior also considers social norms and personal beliefs as input factors to influence compliance behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Kamleitner et al. (2012) developed a framework, much like Ajzen (1991), although applied specifically to small business taxpayers, which considers social norms and personal beliefs to have a direct and indirect impact on small business owners’ tax behavior and compliance.

From an institutional perspective, Kirchler (2008) introduced an extension to classical standard utility theory, known as the “slippery slope” framework. One of the underlying assumptions of this framework is the perceived power of the authorities to carry out punishment for tax evasion and the taxpayer’s observation of the resources put forth to ensure the government can enforce compliance. Taxpayers must also have trust in the establishment, believing that the authorities are putting their tax dollars to good use (for the benefit of the people) and that they will deliver on any promises of punishment for noncompliance. This approach highlights the trade-off between power and trust in varying levels of compliance.

Kirchler (2008) suggests that when institutional power and trust in the institution are low, taxpayers are more likely to evade. When evasion is high, the government needs to reestablish power through means of punishment to move the taxpayer into a state of enforced compliance. Taxpayers have less incentive to evade when in a state of enforced compliance because they see the effect of diminishing returns. When power is low, increasing trust can lead to increased compliance. When power and trust are both high, there are different degrees of enforced and voluntary compliance. Both constructs moderate each other along a continuum that slopes downward. Evidence in other research, where trust in public authorities (Alm & Torgler, 2004), government quality and spending effectiveness (Barone & Mocetti, 2011), and government fairness (Cummings et al., 2009) all contribute to the institutional factors that directly influence tax compliance.

IRS Compliance Presence and the Small Business

It is a common misconception, fueled by misleading propaganda, that the IRS is dispatching agents to conduct mass audits and ramp up enforcement. In fact, for all tax returns filed between 2014 and 2022, only 0.4% of individual returns and 0.66% of corporate returns were examined (Faulkender et al., 2025). A significant decline in examinations since 2015 is evident in IRS data. Where definitive data on the number of small business filers under audit or examination is complex to track down, the audit rates for small businesses are generally higher than those for individual filings. Sole proprietors with over $1 million in gross receipts see about a 4% audit rate (Melick, 2025). Considering the total individual audit rate is less than 1%, this is significant to this group of taxpayers.

The audit rate for small business taxpayers tends to be higher because the IRS has assessed the likelihood of errors and omissions among this group to be high. Complex income and deduction rules can be a barrier to small businesses (Freudenberg et al., 2012). Research suggests small business taxpayers are most likely to cheat on their taxes (Kirchler, 2008). Small businesses tend to be centered around one individual who is reliant upon the success of the operation (Hankinson et al., 1997). Psychological factors relating to business success can play an important role in testing the boundaries of compliance (Kamleitner et al., 2012).

The relationship between the taxpayer and the government is another factor to consider when discussing small business audit rates and tax compliance. The Comprehensive Taxpayer Attitude Survey, conducted in December 2024, measured compliance intention based on trust in the IRS as an institution to help educate and resolve tax matters, as well as the taxpayers’ motivation and capability to comply (RESEARCH, APPLIED ANALYTICS & STATISTICS (RAAS) et al., 2024). Survey results show that trust and satisfaction with the IRS declined sharply from data collected in 2022. These are the very factors that are at the core of tax morale. A majority of survey participants agree that “burdensome” tax law is a barrier to compliance. Only roughly 50% of participants have the motivation and the capability to comply with the United States’ complex tax system. While the study did not specifically target small business owners, it is fair to assume the principal acting on behalf of the business could harbor these exact beliefs.

When defining small businesses, we look mainly to those taxpayers who file as sole proprietors, other flow-through entities like S-Corporations and Partnerships, and small corporations that fall into the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) definition with gross receipts of less than $25 million over three years (IRC § 448(c)). These entities make up approximately 99.9% of all American businesses (Advocacy, 2024). The decision-making responsibility typically rests with one individual, who is the principal manager, owner, or a group of related individuals with a controlling interest in the business operations (Kamleitner et al., 2012).

A 2019 survey revealed that 70% of small businesses do not employ an outside accountant to assist with financial matters (Brown, 2025). Many small business owners attempt to handle tax compliance matters on their own and are often overwhelmed by the situation. When outside counsel is not sought, an individual’s social, personal, and perception of institutional factors come into play, preventing the swift resolution of often mundane inquiries. As many professionals can attest, notices are often not answered promptly, which can lead to more complex issues with the IRS. Small business owners can address IRS correspondence on their own, but the principal must remain diligent and follow through with communication.

The next section will introduce four (4) cases of actual client experience with IRS issues and how they were handled. We present to you the facts, analysis of applicable law and procedure, and how the issue was successfully resolved. By demonstrating actual client cases, we hope to demystify resolution options and provide small business taxpayers with confidence that maneuvering the complex US tax system is possible and a positive outcome is attainable for the most common business compliance issues.

Case Examples

Case #1 – “Timely mailed is timely filed”

Facts

Partnership X is a small business with four partners. For the 2022 Tax Year, they mailed a Form 7004 (Request for automatic extension to file) to the IRS on March 14, 2023, and filed their Form 1065 (U.S. Return of Partnership Income) on August 14, 2023. They then received a Notice CP-162A, dated August 21, 2023, from the IRS informing them that a Failure to File penalty of $4,400 has been assessed on their Form 1065 for the Tax Year ending December 31, 2022. According to the Notice, Form 1065 was filed five months late. The alleged late filing came as a surprise to the Partnership since filing the extension should have given them until September 15 to file their Form 1065. Upon double-checking, the owners confirmed that they had mailed a Form 7004 (Request for Automatic Extension to File) on March 14, 2023, by certified mail to the IRS, as advised by their accountant.

Analysis

When an IRS notice is received, the first step is to read it carefully. These notices are intended to inform the taxpayer of the IRS’s position on a matter and outline the taxpayer’s right to respond to or protest the assessment (Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service, 2021). While the IRS does offer some options for requesting penalty abatement, these options should be reserved for cases where the penalty is valid, not when the IRS has made an error. Instead, the facts listed in the notice are compared first to the taxpayer’s records of what was filed and paid. Moreover, if a discrepancy exists, the taxpayer will want to protest the IRS’s assessment and provide proof of the filing, the amount paid, or the amount that should have been reported to have the penalty or additional tax removed.

A Failure to File (FTF) penalty, also known as a late-filing penalty, is one of the most common penalties assessed by the IRS (Faulkender et al., 2025). For individuals, the penalty is 5% of any unpaid tax as of the date the return was due, with a minimum of $450 and a maximum of 25% of the unpaid tax (IRC § 6651(a)(1)). Moreover, since S-Corporations and Partnerships do not pay tax directly, the late filing penalty for them is based on the number of shareholders or partners per month that the return is late (IRC § 6698 & IRC § 6699). This amount is adjusted yearly for inflation, with the penalty being $220 per shareholder/partner per month for Tax Year 2023.

This penalty should only be applied if a late filing occurs. In this case, the Partnership had properly mailed an extension for time to file one day before the typical deadline of March 15 for Form 1065. Even if the IRS receives the extension form after March 15, it is supposed to accept it as timely filed under the “Timely mailing treated as timely filing and paying” rule (IRC § 7502). Under this law, the IRS is to treat a tax filing or payment as submitted on the date of the postmark if submitted through the United States Postal Service (USPS) or a Private Delivery Service that the Treasury Department has deemed as an accepable alternative to the USPS.

Once it is determined that a penalty was assessed in error, it is essential to decide how to respond to the IRS. Depending on the specific IRS issue, the taxpayer may have the option to call to provide additional information, or they may be required to submit a written protest. An IRS notice will either state within its body where a response should be submitted or, if not, send a response to the address at the top of the notice. In either case, it is essential to have documentation that supports the taxpayer’s position. This documentation is crucial, as the burden of proof typically falls on the taxpayer (IRC § 7502).

Resolution

Upon reviewing the facts, the Partnership did file its business Form 1065 for 2022 in a timely manner, but it had been assessed a late filing penalty due to the IRS not acknowledging receipt of the extension to file that was mailed on March 14, one day prior to the deadline. We knew that the issue was likely with the extension and not Form 1065, based on the information provided in the notice. In the notice, the IRS states that the return was filed five months late. However, since the notice was dated August 21, 2023, the return was received before the extended deadline of September 15, 2023. Therefore, the IRS must not have an extension to file in place, as they are calculating the penalty based on the original deadline of March 15, 2023.

To resolve this issue, we contacted the IRS, and the representative who answered confirmed that the IRS did not have a record of the extension on the Partnership’s account. We then explained that we had proof that the extension was mailed on time. During the call, the IRS Representative provided their fax number so that we could send them a copy of Form 7004 and the certified mail receipt dated March 14, 2023. With the form and proof of timely mailing provided, the IRS Representative was able to grant the missing extension and update the business’ account. In turn, this caused the IRS’s system to recalculate and remove the late filing penalty. By calling first, we were able to save time by not submitting a written response and getting the penalty fully removed within two to three weeks. Also, by having the IRS correct their errors, this method of resolution preserves the taxpayer’s history of tax filing compliance, which leaves them in a better position for penalty abatement requests if needed in the future.

Case #2 – Misapplied Payment

Facts

Business Z is an S-Corporation that handles its payroll in-house. They are a weekly depositor and make all payroll tax payments from their business checking account. They received IRS Notice CP134B dated March 4, 2024, informing them that they had a balance due on their Form 941 (Employer’s Quarterly Federal Tax Return) for 2023 Q4. The notice indicates that the tax was underpaid by $16,889.10 and that late payment penalties, failure to deposit penalties, dishonored payment penalties, and interest total an additional $2,357.41. However, the owner was not previously aware of any other issues with payroll deposits for that period.

Analysis

The IRS requires that employers withhold certain taxes from their employee’s wages and remit them on a timely basis. While the exact timing of these deposits varies based on the number of employees and total tax liability, the IRS imposes a specific penalty, “Failure to Deposit,” if these deposits are not remitted on time (IRC §6656). This penalty starts the day after the tax deposit is due and ranges from 2% to 15% of the unpaid tax. This is in addition to the standard interest and Failure to Pay Penalty (IRC §6651), which is 0.5% per month, up to 25% of the unpaid tax.

In addition to the timely remittance of payments, it is also important to use the correct tax form and period. Otherwise, once the relevant tax return is filed, the payments will not match the reported tax liability and, in turn, will cause the IRS’s system to assess penalties and interest automatically. The IRS maintains a separate account for each tax form and period within the overall taxpayer’s account, and the system is not sophisticated enough to identify payments made to the wrong tax form or period. However, the IRS does allow taxpayers to access and download transcripts from its website (Business Tax Account, Internal Revenue Service, n.d.). Specifically, the Account Transcript will display all payments, taxes reported and assessed penalties for that specific form and period. Transcripts provide valuable information on what is causing a particular notice or penalty.

Resolution

To gather more information, we accessed and downloaded the business’s account transcripts. A review of the account transcripts revealed several issues. One issue was that the payment of $1,247.74, which was due on November 22, was missing. Second, the payment of $9,178.06 made on December 14 had not gone through and had been canceled. Moreover, the payment of $6,463.30, which was paid on January 12, had been posted to the Form 941 2024 Q1 account by mistake. After gaining a clearer understanding of what had happened, the owner made the two outstanding payments to the account.

The next step was to call the IRS’s business line. The IRS Representative was able to access the account and make a verbal statement that the payment of $6,463.30 made on January 12, 2024, needed to be moved from Form 941 2024 Q1 to Form 941 2023 Q4. The advantage of making this payment rather than paying the additional balance and receiving a refund later is that it preserves the original payment date. This, in turn, causes the corresponding penalties and interest to be recalculated and removed once the correction is processed. In this case, that saved approximately 40% of the originally assessed penalties and interest. Overall, this case took about four weeks to resolve, as the IRS’s system first had to move the payment and then recalculate the interest and penalties.

Case #3 – Unexpected Refund

Facts

Business Y is a small privately held C-Corporation that files a Form 1120 (U.S. Corporation Income Tax Return) and has a fiscal year end of March 31. In August of 2024, they received two unexpected refund checks from the IRS for $210,511 and $130,371.68, respectively. On the checks, it indicated that they were from their March 2023 tax year. They were not expecting any additional money from this tax period, as they had already received their expected refund several months prior. They investigated further by reviewing their account transcript for the March 2023 tax year and found that two payments of $210,000 and $130,000 were posted to that tax year in error. However, those payments were intended to be their extension payments for the March 2024 tax year. Furthermore, if that mistake is not corrected, it would result in an underpayment of their March 2024 taxes.

Analysis

The IRS requires taxpayers to pay their income taxes in full by the non-extended filing due date and often through estimated payments during the year. These payments must be made according to the specific form and tax period and can be paid by mailed check, direct deposit with a bank account, or the Electronic Federal Tax Payment System (EFTPS). The IRS will assess penalties for Failure to Pay Tax Shown on the Return (IRC § 6651(a)(2)) and Failure to Pay Estimate Tax (IRC § 6654 & IRC § 6655), both of which are based on how late the payments are.

As mentioned in Case #2, the IRS maintains a separate account for each tax form and period. Problems can arise when payments are not made to the correct tax period. Suppose the payment is made to an earlier tax period that does not have an outstanding balance. In that case, this can result in a credit balance, which the IRS’s system will automatically refund back to the taxpayer. Since the Failure to Pay and Failure to Pay Estimated Tax penalties are based on the late receipt of payment, simply cashing the refund and making a new payment to the correct account has the potential to incur significant extra costs in the form of penalties and interest.

The taxpayer should return the refund check and request that the misapplied payment be moved to the correct tax form and period. To do this, they need to write “void” across the front and back of the refund check and mail it back to the IRS with a letter explaining the mistake and which payment they need moved (Topic No. 161, Internal Revenue Service, n.d.). It is important to list the exact payment amount and date so that the misapplied payment can be located in the IRS’s system. If possible, including the EFTPS number or other proof of the original payment can also help ensure that the correct payment and amount are moved between the accounts.

Several IRS locations handle refunds, so it is also important to look up which IRS center to mail the refund check back to (About Form 3911, Internal Revenue Service, n.d.). The check will usually list the city of the IRS location that issued the refund, and that should match the Refund Inquiry Unit for the taxpayer’s state of residence. With all written correspondence to the IRS, the voided check and cover letter should be mailed via certified mail or a similar option that provides a tracking number. By returning the refund and having the original mistake corrected, the IRS will retain the original payment date in the system, which will prevent penalties and interest from being assessed due to the mistake.

Resolution

To correct this mistake, the C-Corporation needed to return the refund checks and reassign the extension payments to the correct tax year. They wrote “void” across the front and back of the refund check and mailed it with a cover letter explaining that they were returning the refund and wanted the payments of $210,000 dated July 11, 2024, and $130,000 dated July 15, 2024, moved to their March 2024 tax year. Correspondence was sent via certified mail so that they would have proof of the delivery to the IRS. Their representative then called to follow up on the correspondence to make sure that it was received by the IRS and that the payment was subsequently moved to the correct tax year. It was, but this process took about three months to be fully resolved.

Case #4 – First Time Abatement

Facts

Partnership A is a small business that has always been compliant with its tax filing requirements. It was converted into a single-member LLC on April 1, 2022, and continued to operate with a calendar year-end tax year. They informed their accountant of this change in early 2023 during a meeting to begin preparing their tax returns. Their accountant informed them that they would have to file a final Form 1065 (U.S. Return of Partnership Income) for January 1, 2022, to March 31, 2022, and an initial Form 1120-S (U.S. Income Tax Return for an S Corporation) for April 1, 2022, to December 31, 2022. They filed both Form 1065 and Form 1120-S on March 6, 2023. They did not realize that anything was wrong until they received an IRS notice LT38 dated March 4, 2024, informing them that they had been assessed a late filing penalty on their Form 1065 for the tax period ending March 31, 2022. According to the notice, they had a total amount due of $6,111.82. Upon calling the IRS, they learned that the balance was due to a Failure to file penalty.

Analysis

Tax return filing deadlines are typically three to four months beyond the end of the tax period, depending on entity type (Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service, 2025). Because the business converted to a single-member LLC on April 1, 2022, they created an additional filing requirement for the short year ending March 31, 2022. The filing deadline for partnerships is the 15th day of the third month following the year-end, so in this case, the filing deadline was June 15, 2022. Since the IRS did not receive either the tax return or an extension to file request by that date, the IRS is correct that they can assess a late filing penalty under IRC § 6698. Note, this is one reason it can be valuable to consult tax professionals regarding changes in business structure or ownership.

When late filing is evident, there is no option to prove that the IRS is wrong in assessing the penalty. However, it is the IRS’s policy to grant penalty relief by administrative waiver under certain conditions (Administrative Penalty Relief, Internal Revenue Service, n.d.). These waivers are not part of the tax law but rather policies and procedures that the IRS follows when exercising its authority to collect and enforce tax laws. The IRS makes its policies and procedures publicly available through the publication of the Internal Revenue Manual (IRM) (Parnell, 1979). The IRM outlines the IRS’s policies and procedures that IRS employees are expected to follow when executing their duties, helping to ensure fairness and transparency for taxpayers. The manual serves as a counterpoint to the tax law found in the tax code.

One of the most valuable options for penalty relief is the First Time Abatement (FTA) (IRM 20.1.1.3.3.2.1). Under the FTA, the IRS will grant administrative relief of the Failure to File penalty, Failure to Pay penalty, and Failure to Deposit penalty for a single tax period if the following conditions are met.

-

The taxpayer must have filed and paid all required returns and taxes for the 3 years preceding the tax period that is being penalized.

-

If the same type of return was filed in the preceding three years, then no unreversed penalties of the penalty types listed under this waiver are present in those years.

-

A penalty abatement was not previously granted due to FTA or reasonable cause on the same type of tax return in the preceding three-year period.

Based on these requirements, the FTA intends to provide taxpayers with penalty relief if they have been previously compliant with their tax filings and payments. The request for an FTA can be made either in writing or orally by calling the IRS (Buttonow, 2013). Once requested, the IRS Representative will run a system check to determine the taxpayer’s eligibility for penalty relief. If granted, the FTA will remove all qualifying penalties on the requested form and tax period. So, if a taxpayer had both filed and paid late on a single tax year, the FTA would remove both the Failure to File and Failure to Pay penalties. And despite its name, First Time Abatement eligibility resets after 3 years of complaint filing and payments. So, for example, even if a taxpayer had penalties forgiven under an FTA in 2018, they could still be eligible again for the 2022 tax year (or later).

Resolution

In this case, after determining that the IRS was correct in assessing the late filing penalty, we then reviewed the business’s account transcripts to see if any other penalties had been assessed in the prior three years. They did not have any prior failure-to-file penalties assessed and had filed the prior three years of partnership returns. Knowing this, we called and requested that the late filing penalty be waived under the FTA administrative process. The IRS Rep processed the request on the phone and informed us that the penalty abatement had been approved. The owner then received an IRS notice about 4 weeks later stating that the penalty relief was granted due to a history of good compliance.

Conclusion

This paper presents common notices small business owners may receive, the applicable law, how to resolve them, and advice for taxpayers (Table 2: Summary of Resolution). As all studies have limitations, the most evident one in this paper is that only four (4) case examples are presented. There are limitless cases out there as not all situations are the same for every taxpayer. We chose the most common and easily resolved examples to show taxpayers that notices can be easily handled if they address them timely.

Research into taxpayer compliance has taken various turns since the publication of the first Internal Revenue Code of 1939. Governments continue to seek ways to compel compliance from every group of taxpayers. It has been established that small business taxpayers have a greater propensity to cheat (Kamleitner, 2012), provoking a higher level of enforcement procedures by the IRS. This enforcement response tends to reduce taxpayer morale, due to social and personal beliefs, or possibly a lack of faith in the institution. Small business taxpayers need to cast aside their preconceived notions about tax enforcement and treat IRS correspondence as an evidentiary matter to defend their compliance.

To explain the barriers to resolution, we drew on the concept of tax morale. This is a complex concept (Torgler, 2007) with three main factors inherent in this societal phenomenon: Moral rules and sentiment, fairness, and relationships between taxpayers and the government. Under this overarching concept, researchers have developed theories that address the implications of social and personal norms, economic utility, and the effects of government policy and punishment on the actions of taxpayers. It is our hope that taxpayers recognize these inherent human traits exist and do not let them impede successful IRS procedural resolutions.

As shown in these cases, small business owners have options to protest penalties or seek penalty relief with the IRS. Tax law gives the IRS the right to assess penalties and collect on delinquent taxes, but taxpayers also have the right to respond to or dispute penalties and tax assessments. While IRS notices can be intimidating, they contain valuable information about what the issue is and what options the taxpayer has for responding. By carefully examining these details, it can be determined if the IRS is correct in its assessment or if there is an underlying issue that the taxpayer can dispute. By following the IRS’s procedures and providing adequate documentation, many common IRS issues can be resolved favorably for the taxpayer.

While the average small business owner cannot be expected to be an expert in tax law or IRS procedures, having a basic understanding of these topics can go a long way in resolving IRS issues. Successful disputes regularly rely on good documentation of the tax filing or payment being done correctly. Even if the taxpayer wants to hire an expert to help them with an IRS issue, options could be limited if adequate documentation is not retained to support the taxpayer’s position. By understanding what can serve as proof before the IRS, taxpayers can maintain adequate records to avoid any issues that may arise, which can then be provided to the IRS directly or through their representative.

Furthermore, with the current turbulence surrounding the federal government, it is even more important for taxpayers to understand their rights before the IRS. While there has previously been a push for a “kinder, gentler” IRS, this could be undermined if the current administration prioritizes more automated penalty assessments and increased collection actions. By educating themselves, taxpayers can assert their right to respond and dispute any incorrect assessments or seek penalty relief through the available administrative waivers.