Introduction

This study investigates the usage, dependency, and relationships around payment credit terms (trade credit) in the financing of private small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the United States of America (US), and whether the lack of external financial transparency plays a role in such decisions. The economic importance of SMEs has been widely documented. In the US alone SMEs are responsible for 43.5% of GDP, 45.9% of the workforce, and 99% of all businesses (SBA, 2024). Against this background, many governments continue to gradually develop favourable policies towards SMEs to lower barriers to their development.

Prior studies have identified a ‘finance gap’ with SMEs facing difficulties accessing affordable capital at the start-up stage and beyond, often compounded by a low participation rate in various government initiatives intended to encourage financial investment (Collis et al., 2016; Ghulam et al., 2025; Melnick, 2021; Shields et al., 2024). The relative lack of transparency compared to larger entities results in fewer financing opportunities as potential lenders face higher assessment and monitoring costs, particularly in volatile economic environments (Berger & Udell, 2002). As a result, SME investors tend to be the owner-managers themselves (Carsberg et al., 1985; Collis, 2003, 2008). While there is some limited international literature on the users of SME financial statements, the focus has been on lenders, and little is known about the information needs of suppliers, trade creditors, or third parties.

Small business representatives have long complained about the perceived excessive burden of financial regulation (Minnis & Shroff, 2017), leading to a concerted push to reduce reporting requirements in the European Union (EU), United Kingdom (UK), Finland, South Africa, and IFRS. Most recently the UK reduced financial reporting and audit requirements for 133,000 SMEs (UK Company Size Thresholds Have Increased, 2024). This reduction in financial information could make it more difficult, or expensive, for SMEs to obtain trade credit and/or bank financing as potential lenders expend additional expense completing due diligence. The US by comparison provides an interesting counterexample of an unregulated market for accounting information (Collis et al., 2013; Minnis & Shroff, 2017), where private limited liability SMEs are largely exempt from mandatory financial reporting requirements. Trade credit decisions in the US are typically made in the absence of accounting information unless one party has the economic leverage to demand such information.

While most scholarly work on the finance gap faced by SMEs is focused on bank loan loss provisions, or to a lesser extent equity, not all businesses borrow from banks and fewer still seek outside equity. Studies in various countries have found that SME trade credit use is of the same order of magnitude as bank borrowing (Berger & Udell, 2006; Forbes, 2010; Paul & Boden, 2011). Trade credit provides a cushion during credit crunches, monetary policy contractions, and other events that leave financial institutions less able or less willing to provide small business finance. Since SMEs have limited access to commercial bank lending, trade credit is often the primary source external working capital financing. Despite trade credit’s critical importance to SMEs, it has received much less attention than commercial bank lending.

This study focuses on the US, where SMEs are not required to publish financial statements or have their accounts audited. Our study is novel as the existing literature on trade credit focuses primarily on international SMEs with different financial reporting requirements. Our results find that US SMEs compensate for the lack of financial reporting information by relying on their relationships with and reputation of their suppliers and customers when granting trade credit. While SMEs are reliant on this soft information, they remain resistant to providing financial statements and as a result lack access to more formal (bank) financing (Berger & Udell, 2006; Cornée, 2017).

Literature Review

The existing literature on payment terms and SMEs is severely limited and mainly comprised of studies that look either at a single country or a conglomerate of politically and economically tied countries that fall under the same accounting standard and where the differences of social, cultural, and economic conditions can vary drastically from the US. Despite this, Collis et al. (2016) synthesised the concepts and categories from these country level studies to identify a range of themes that impact SME payment terms decisions internationally:

-

The importance of trade credit

-

The importance of economic conditions

-

Trust, reputation, and personal relationships

-

The importance of financial statements

-

Information vs relationship-based lending approaches

-

Cash and cash management

-

The types of information used within payment terms decisions

Importance of Payment Credit Terms

“The importance of trade credit to SME financing is a compelling reason to include it as a lending technology, although it is not delivered by financial institutions.” (Berger & Udell, 2006, p. 2951).

The use of trade credit is not new; it has been recognized as a form of interfirm relationship since the nineteenth century, helping merchants receive short-term credit when loans from the bank were not an option (Meltzer, 1960). As one of the early studies on this topic, Meltzer draws upon US data and economic conditions of the late 1950’s for manufacturing firms and notes how tighter monetary policies disproportionately affected small firms which in turn made them rely more heavily on trade credit (1960). “In most business transactions, products and services are sold on credit rather than cash, which creates accounts receivables and represents trade credit. The amount of trade credit (payment duration) granted to customers is a key characteristic of credit terms that is influenced by industry-standards, market power, financial constraints, and strategic choices among other factors” (Lefebvre, 2023, p. 1316).

Trade credit has some important characteristics that make it an essential complement, and at times a substitute, to bank lending. Trade credit, even when not utilized, is a largely accessible option to many SMEs. Trade credit terms vary from industry to industry, from place to place and even from supplier to supplier. Early payment discounts and differential pricing can at times be offered to sweeten the deal for both the supplier and customer into taking the trade credit offered (Petersen & Rajan, 1997). Nevertheless, credit is often cheaper than bank borrowing as a form of finance, and it has the advantage of being a flexible form of credit that tends to expand with the volume of business and has a capacity for absorbing unexpected shocks.

Importance of Economic Conditions

Prior to the effects on financial lending created by the Covid-19 pandemic, both Casey and O’Toole (2014), along with Bussoli, Giannotti, Marino and Maruotti (2022), considered such ramifications following the 2008-9 financial crisis on European SMEs and the increased use of trade credit, further amplified by Pattnaik, Hassan, Kumar, and Paul’s research (2020). This previous research clearly shows how SMEs have limited protection against recessions and economic downturns. Such economic headwinds cause difficulties in maintaining or expanding business and financing is squeezed because banks become unwilling to lend, suppliers reluctant to grant credit and customers have taken more credit by deferring payment.

Much has been made of the role of SMEs in job creation and growth, and without access to appropriate finance, business expansion is often a problem for SMEs in many countries. The high rates at which SMEs are both created and disappear is a factor everywhere and impacts their ability to borrow and obtain credit (Berger & Udell, 2002, 2006). Credit risk is the fundamental driver that determines the structure of transactions, but different businesses have different methods of dealing with it in different environments. DeYoung, Gron, Toma and Winston (2015) highlight this issue, where credit can become less readily available by bank lenders who are taking “risk-adverse actions to conserve equity capital. Such behavior by banks can exacerbate economic downturns by restricting credit to job-creating small businesses” (DeYoung et al., 2015, p. 2483).

The Role of Trust, Reputation and Personal Relationships

Earlier studies emphasize that when SMEs engage in business transactions, the availability of trade credit is primarily influenced by trust. This trust may stem from personal relationships, the reputation of the businesses or their owners, prior trading history between the firms, or other external qualitative factors (Meltzer, 1960; Murro & Peruzzi, 2021; Otto, 2023). The reliance on trust, reputation, and personal relationships as social capital was not confined to one industry, sector, or country – extending across borders and continents to encompass all businesses.

Trust is an efficient, low-cost governance mechanism in the situations where it can be relied upon (Gulati & Nickerson, 2008; Rus & Iglič, 2005). Collis et al. (2013, 2016) suggest that trust was more likely to operate where there was a local close-knit community and qualitative information about the contracting parties, such as reputation for quality of work or ethical dealing, were available. One predisposing factor to use of trust is the knowledge that breaches of trust will be severely penalised, for example by social ostracism or loss of good reputation and, hence, future business opportunities (Howorth & Moro, 2006).

There is a level of give and take for every company that utilizes even a small portion of trust when making trade credit decisions for both their customers and suppliers. “Recent research has theorized that trade credit builds mutual commitment and trust between a receiver and a provider, forming closer and stronger relationships between them” (Astvansh & Jindal, 2021, p. 784).

Regulation & Importance of Financial Statements

Privately held SMEs operating throughout the globe face widely different accounting regulations. Within the US, small and medium-sized private companies registered in any state are not obliged to publish financial statements nor have their accounts audited. This contrasts with counterparts registered in the UK or EU, where they are legally required to prepare periodic financial statements for their members and publicly file these accounts with a public registrar. These differing accounting frameworks for private companies create varying levels of access to financial statement information, and as result, impact the role of such of such information within payment credit terms decisions.

Within jurisdictions that have a public filing requirement for private company accounts, there is minimal evidence about how suppliers and customers of SMEs use the published financial statements in credit decisions (Collis et al., 2013). In the UK, companies register their annual reports and accounts at Companies House, but there is no record of who accesses these reports. Empirical evidence (Collis, 2008) shows that the directors of SMEs in the UK believe that the main users of their published accounts are suppliers and other trade creditors, credit rating agencies, competitors, followed by the bank/lenders, and customers.

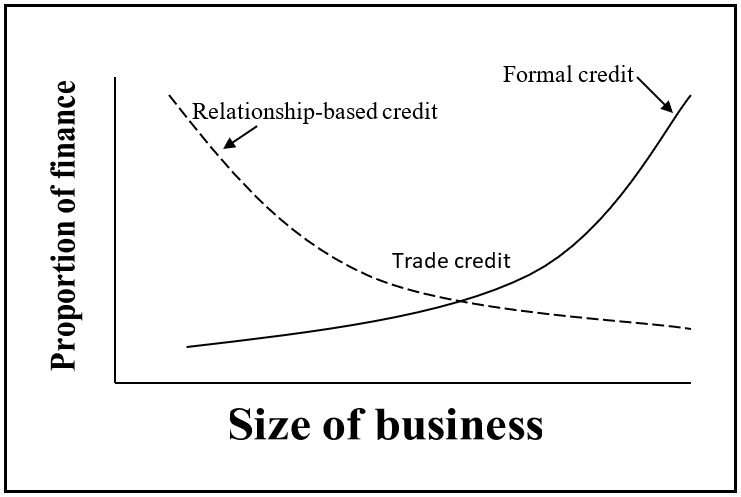

Regardless of whether SMEs face mandatory accounting requirements, prior research shows that where SMEs contract only with other small entities, relationship-based credit relationships are most important. However, when medium- and larger-size entities contract with each other or with small entities, information derived from financial statements becomes an important part of the transactional lending approach used in the SME sector. When SMEs do directly evaluate financial statement data from other entities, it is often used critically — as an analytical tool, applied with skepticism and cross-evaluation (Collis et al., 2016). Lines such as inventory are perceived to be easier to manipulate by preparers, so a stronger focus on cash, investment and distributions (by way of dividend or owners’ pay) were of more interest, as were turnover and turnover growth calculations.

Information vs Relationship-Based Lending Approaches

Research already highlighted has shown that the approach SMEs take to finance transactions differ across countries. As will be discussed further, many SMEs can utilize relationship-based (opaque, “soft”) finance as a complement or substitute for the information-based lending approach that banks rely on utilizing transparency (“hard”) data (Berger & Udell, 2008). For larger businesses, equity and loan finance are acquired through the more formal process of the information-based lending approach. Financial statements (that may or may not be audited) and well-researched credit reports, together with other information are used in the granting and receiving of any form of credit. It is in the grey area of the middle ground, where SMEs try to access lending from an information-based approach without having the transparency of reliable financials that can leave them feeling the dichotomy of the two approaches.

Berger & Udell (2006) though, find that the viewing of transaction lending as just a homogeneous lending technology is flawed, with borrowers being divided into either the informationally “transparent” or “opaque” buckets. Overlooking these two categories may produce not only misleading research, but also policy conclusions. It is not an either/or setup of information versus relationship basis when it comes to trade credit, but a combination of both in conjunction with small business credit scoring at times that allows for the overcoming the disparity of information availability (Cornée, 2017). The collection of “soft” information through the building of relationships and a history of reliance, can be used because “ethical perception of the borrower plays an important role in reducing agency problems such as moral hazard and adverse selection” (Collis et al., 2013, p. 6). Trade credit in the United States provides to SMEs the same, if not more, cash flow, compared to bank loans (Murro & Peruzzi, 2021). Financial crises do not increase the amount of loan availability, with banks becoming more focused on risk-adverse actions and it is the limitation of funds available to SMEs that in turn further harms the financial climate by reducing the ability of SMEs to influence the growth of communities and the financial prospects on an individual basis (DeYoung et al., 2015; Meltzer, 1960; Palacín-Sánchez, Canto-Cuevas and di-Pietro, 2019).

Figure 1 illustrates how relationship-based trade credit and formal credit may develop for SMEs depending upon their size (Collis et al., 2013, p. 24). When neither micro nor large, but at an intermediate size, it may be that the business has outgrown its access to relationship-based credit but is not yet able to replace it with formal credit, giving rise to a ‘trade credit gap’.

Cash Flow Management

The Wu-Tang Clan may have been the ones to lament how “Cash Rules Everything Around Me (C.R.E.A.M),” but this sentiment easily bleeds into the private SME sphere (Wu-Tang Clan, 1993). The ultimate goal of most transactions is cash realization, and lending technologies that accelerate this process help reduce financing costs, allowing businesses to reinvest sooner, supporting higher transaction volumes. One common method is to require customer deposits or full prepay, particularly for long lead time, custom-made products that cannot be easily resold if the buyer fails to complete the purchase.

Large companies often use their dominance through economic leverage to delay invoice payments (Petersen & Rajan, 1997; Wilner, 2000). Although this can create significant financial strain for smaller businesses, it may be a trade-off worth considering if the relationship supports the growth of the smaller firm. “A firm seeks trade credit from its suppliers for the same reason that customers seek trade credit from the firm—it allows the firm to delay payments that it owes its suppliers. Such delayed payments decrease the firm’s costs and increase the firm’s profit. Because profit increases firm value, received trade credit indirectly increases the firm’s value through increasing its profit,” (Astvansh & Jindal, 2021, p. 782).

Effective cash management requires companies across all industries to understand how both the giving and receiving of trade credit affects the bigger picture of current liquidity and long-term company value and its ability to strategize its cash allocation (Astvansh & Jindal, 2021). “Emerging from the field of Banking and Finance, research in trade credit has evolved as a multi-disciplinary scientific domain with contributions from Business Management, Industrial Engineering, Production and Operations, Finance, Economics, etc.” (Pattnaik et al., 2020, p. 1).

The Types of Information Used Within Payment Terms Decisions

From the analysis of the literature so far, it is clear that in order to access cash, the two primary approaches for lending decisions are information- and relationship-based. These approaches can be utilized on their own or can be weaved together through contingency factors when making payment term credit decisions. Contingency factors are the situational variables that influence how organizations operate and make decisions. They mean that there is no single “best way” to manage, but rather that effective practices depend on the context (e.g., size, technology, environment, strategy, or regulation) (Collis & Hussey, 2013). Collis et al (2013) indicate that these contingency factors influence the extent to which hard/formal information versus soft/informal information is used by SMEs in trade credit decisions. The relationship between the three categories is illustrated in Figure 2.

Use of Hard/Transparent Information Derived from Formal Reports

Prior research has identified that the main formal sources of information in many countries are the financial statements and data supplied by credit rating agencies and credit insurers (Collis et al., 2013, 2016). In addition, in many countries the customer’s assets and the overall cash position were considered as important indicators of trade credit risk for larger SMEs in the study that analyse their customers’ financial statements. In the USA, given the absence of published financial statements, formal information typically comes in the form of data accessed from a company such as Dun & Bradstreet (D&B) that can provide business data, analytics and insights regarding a company’s creditworthiness, financial stability, and trade credit payment history that can bleed into the area of non-financial information and information intermediaries. Other formal sources of information include information found on the customer’s website about organizational behaviour and company policies.

The Usage of Soft/Opaque Information

In terms of soft information, the literature highlights that trust is a significant feature of the trade credit decision, and this was apparent even in the small unincorporated entities where the credit period was very short (typically, payment on invoice). This stems from the importance of ‘soft’ information derived from personal relationships and networking and the length of the business relationship. In larger SMEs, it also included organisational behaviour such as the payment history. Small companies seemed to avoid risky customers by relying on a variety of ‘soft’ forms of information, including the reputation of the customer and by observing certain behavioural patterns in customers such as the attention paid by the customer to the supplier, answers given to questions by the customer, or the flexibility and expertise in the subject shown to the supplier in the contract negotiation. “Studies carried out before the outbreak of the 2007 financial crisis suggest that getting rid of soft information was economically well founded. Yet, the subprime mortgage crisis dramatically highlighted the limits of not considering soft information” (Cornée 2019, p. 714).

The Importance of Non-Financial Information and Information Intermediaries

With private companies in certain jurisdictions being “informationally opaque” to outsiders, there has been considerable research into whether there is an effective and efficient manner for determining the credit worthiness of such entities. Small Business Credit Scoring (SBCS), which utilizes a combination of the limited data available on the company in conjunction with personal consumer data on the owner, alongside D&B and other historical transaction information, allows the granter of the credit to assess the default risk of the applicant (Berger & Frame, 2020; Wang, 2021; Cornée, 2019).

Information intermediaries, such as D&B, have had an important role in collating information and using their expertise to analyse it. While some very small businesses did not use credit reference agencies, their use seemed to become more widespread as enterprises got larger, although they were not used for all transactions. Credit reference agencies and credit insurers provide a useful stewardship role. For example, the knowledge that poor payments to suppliers will be picked up by credit reference agencies and will result in a down-grade in credit score was a powerful factor driving good behaviour among customers.

While more used by lenders on a grander scale, our research showed that trust (and soft information) often carried more weight than any limited financial data that would be given to them – and that to some, credit scoring was not seen as useful, helpful, or truthful.

Contextual and Contingent Factors

While the literature finds that formal report-based and soft information are important determinants of the payment terms decisions (Collis et al., 2013), these can be moderated by the presence of contingent factors. Most prevalent of these contingent factors is the relative size of supplier and customer, reflecting the economic power dynamic that larger customers have over the smaller one. From their international study, Collis et al. (2013) suggest that information availability and the relative economic power balance between supplier and customer affects the overall availability of trade credit.

The Accountability of Private Limited Liability Entities

This study focuses on the US, where small and medium-sized private limited liability entities with no form of public accountability have no state or federal legal requirements to publish financial statements nor have their accounts audited. This focus adds to the body of knowledge, as most of the existing literature on payment terms decisions draws on data collected from SMEs operating in other jurisdictions where requirements differ for financial reporting.

For the purposes of this US-focused study, a private company is defined as a privately owned, limited liability entity with no form of public accountability. Private companies may issue stock and have shareholders, but their shares are not issued through an initial public offering (IPO), do not trade on public exchanges, and are not typically subjected to SEC filing requirements. SMEs, according to the US Small Business Administration (SBA), are manufacturing companies with 500 employees or fewer, and most non-manufacturing businesses with average annual receipts under $7.5 million (SBA, 2024). In 2023 there were 34,752,434 small businesses in the US (SBA, 2024) which suggests that discovering more information about the role of payment terms credit for such entities is required. As prior research has shown, the definition of “small” varies widely between jurisdictions (Collis et al., 2013, p. 2016), but this paper concentrates on data collected from SMEs that fall within the US SBA’s definition of the term. A small number of private companies with over 500 employees were also included in this study to provide additional context of whether the issues that emerged were size or industry dependent.

Internationally, most small and medium-sized businesses operate as unincorporated entities, but the US is quite different due to the more litigious nature of business interactions (see Collis et al., 2013 for more detailed discussion about the reasons for international variations in the legal structures of SMEs). The SBA’s Office of Advocacy (2024), taking data from the Census Bureau’s 2021 Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB)'s data (2023), reported that 86.3% and 13% of total US small non-employer and employer firms, respectively, were structured as sole proprietorships. In contrast, S-corporations accounted for 53% of small employer firms, with C-corporations, partnerships, and limited liability partnerships rounding out the remaining. These statistics are potentially misleading, since the SUSB categorizes businesses based on their federal tax classification rather than their state-level legal structure. As a result, the total number of sole proprietorships recorded by the SUSB includes both unincorporated entities and, the more common, limited liability company (LLC).

LLCs serve as a hybrid between a corporation and a partnership/sole proprietorship legal setup, with its taxation more closely following S or C-corporations. A wide range of US small businesses are registered as LLCs due to simplicity and the limited liability protection it provides for its owners. It allows for single-member formation – either by individuals or corporate entities – and are not required to issue shares. Many LLCs for SMEs in the US are owner-operated.

A more in-depth investigation of trade credit was conducted by the Federal Reserve Board collaborating with the National Survey of Small Business Finances (NSSBF) for 4,240 US small businesses and found that trade credit was used by 60% of small businesses in 2003, an incidence of use that exceeded all other forms of financial services except the use of normal bank accounts. Use of trade credit varied with firm size, increasing from about one-third of the smallest firms to more than 85% of the largest firms. Young firms were less likely than others to use trade credit, and its use was most common among firms in construction, manufacturing, and wholesale and retail trade (Mach & Wolken, 2006).

Summary of the Literature Review

While the existing literature provides insight into the overall importance of trade credit and payment terms within SMEs, limitations do exist due to knowledge gaps surrounding private companies within the US and other jurisdictions where private limited liability entities are not required to produce and publicly file financial statements of some type. As previously indicated, the purpose of this study is to address this gap by providing empirical evidence on the importance of the financial statements of private limited liability US SMEs in the context of payment terms decisions that support customer/supplier relationships. This paper investigates the following research questions:

-

What role do payment terms play in the financial setup and decisions of US SMEs?

-

What factors influence the decision-making process for requesting, granting, and using payment terms?

-

How is the balance between hard/transparent and soft/opaque information reflected in the decision-making process for trade credit?

-

How do the findings from this US-based study compare with those reported in previous international research?

The next section explains the research design and methods chosen for collecting and analysing the data. It then provides an overview of the findings from a variety of viewpoints. In the final section we discuss the contribution and limitations of this research.

Methodology

To investigate the role of payment terms credit and address the research questions outlined earlier, this paper focuses on the transactions occurring between businesses for timing of payments. Qualitative data were collected via 42 in-depth, semi-structured interviews in the USA:

-

Interviews with 39 unique private companies providing trade credit, with 3 additional interviews with secondary participants at three of the companies

-

Interviews with 3 companies outside the parameters: an economic lender, a credit rating agency, and a credit insurance broker. These were not factored into the data but were utilized for supplemental insight.

The entities were selected using snowball sampling, which is a technique based on networking and is appropriate in a study where generalization is not the aim (Collis & Hussey, 2013). As a result, a significant portion of the participants were recruited through personal or professional connections, with a handful through email solicitation. Approximately 75% of the respondents had businesses registered in Colorado, with the rest located throughout the US. Some of these companies were either subsidiaries of a US or international company or they themselves had overseas subsidiaries.

A variety of industries and sizes of companies were sought out to ensure an adequate sample was developed under an interpretivist paradigm. Additional depth or breadth of the sample was limited by company willingness to participate or respond to initial inquiries, especially due to the sensitive nature of speaking about financial matters.

The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured manner, with a list of thematic questions available prior to the interview, and an understanding that not all questions would be asked, depending on the responses given to high level questions.

The use of interviews for the collection of the research data was chosen to allow for efficiency and effectiveness. The use of surveys was initially considered as the primary method, but this approach was discarded due to the extra time required, the inability to easily achieve additional information, and the inability to judge reliability of answers. Most questions were answered, with only a few exceptions due to company policies or non-disclosure agreements (NDAs); in such cases, participants often referred the interviewer to publicly available press releases for additional information.

The questions addressed several areas relating to both internal and external costs involved in business-to-business credit decisions, the approach towards trade credit, and the creation and usage of financial statements. All interviewees were asked to respond based on their company’s current setup or situation, as well as to reflect on changes over the past 5–7 years—including those during the COVID-19 pandemic—that have influenced decision-making. All interviews occurred in the second half of 2024, prior to any global or national economic shifts, such as tariffs, that would have potentially altered responses to some of the questions.

Findings from the Interviews

Analysis from the US interview data provided rich qualitative information that both reinforced findings from prior studies and provided fresh insight into the specific factors that influenced payment terms decisions affecting US SMEs. These findings are presented and explored thematically in order to highlight the specific impact of payment terms on US SMEs.

References to each of 39 companies are made anonymously, as are the quotes from respondent interviews. A unique coding of respondents was created to identify each respondent in accordance with their employment position within the company (see Table 1), the size of their company (see Table 2), and a descriptor of their company’s industry sector (see Table 3). While the size classifications used differ from the official standards used in the US, UK, or EU, they were created to provide clearer distinctions and insights across the range of company sizes included within the interviews.

Economic Power and the Negotiation of Payment Terms

From the interviews it was clear that the economic power dynamic between the lender and receiver of the trade credit was greatly influenced by the relative size and financial set up of the company. Whether the company was cash flow dependent, or had other sources of funding, and what they could bring in terms of influence to the negotiating table drastically altered what terms were offered and taken.

“In manufacturing, credit is life blood.” (SMA Medium, Paper Mfg.)

“I would only work with trade credit suppliers if I could; it is the easiest way to do business and takes the burden off my bank account.” (OM Micro, Furniture Repair)

Terms varied from Prepaid, Net Due, to Net 30, 60, 90 or more – with discounts offered and taken by most if financially able to do so. However, the availability of discounts for early payment varied, with many US companies choosing to keep standard payment terms for all. What a company received from their vendors/suppliers for terms did not always reflect what they offered to their customers, which led to an unbalanced cash flow that could hurt smaller, cash-strapped companies. This could be compounded by the consequences of late payments, which will be discussed in a later section.

For example, one marketing company interviewed described being given Net 90 terms, where the clock started only after a months-long planning process and campaign had wrapped up, which could leave them short on cash for up to a year at times.

Wish for clients to “pay us in advance” [because we had] “finished [a campaign] in April and it has not been paid [by the client]” because of Net 90 terms “which is super painful.” (OM Small, Marketing)

In more than half of the interviews, there was a strong disconnect between the two sides of the business arrangement – with the less economically powerful player side suffering the consequences of larger companies’ inflexible policies or their lack of willingness to meet a small company where they were. Often it was seen that the more powerful player imposed standard terms for all, no matter their size, set up or needs. The implications of this dynamic left SMEs often in the same position as they would find themselves with a bank willing to grant a loan, but with strict adherence guidelines. This follows the same path credit rationing, as highlighted by DeYoung et al. taken by banks during times of financial crises, with at times more expensive or restrictive terms (2015).

“Institutions will just say Net 75 or even feel like they can dictate whatever the hell they want just because they are big.” (SMA Small, Research Equip.)

When it comes to dictating terms, “the big suppliers or the people who just don’t know, they’ll dictate their terms and they’ll say, you take it or leave it.” (SNA Small, Research Equip.)

“Large vendors, they don’t care.” (about offering longer terms to customers) (OM Small, Wholesale Foods)

To encourage timely payments, some of the SMEs interviewed offered their customers discounts, usually in the range of a 2% discount if they paid their invoice within the first 10 days. In terms of being offered discounts, some of the companies interviewed took advantage of early payment discounts whenever available (and when cash flow allowed for it), while others did not see the advantage of the early payment to save a few dollars in the long run.

“We would rather have the runway for the cash than the discount.” (SMA Medium, Cloud IT)

Thus, the discount was deemed as less important than the additional credit period on offer from suppliers, especially since payment terms often represented a large amount of both receivables and payables and provide essential working capital for most SMEs (Silva, 2024; Wang et al., 2022).

In most of the interviews, the US companies that could most effectively dictate payment terms and thereby keep cash flowing in a timely manner had the power of either collateral or mandated services on their side. Collateral could be anything from holding customer’s information on company owned servers, to whether a machine would be repaired in a timely manner. Mandated services were prevalent in especially the education and healthcare industries, where the services provided were mandated by a governing body (at a State or Federal level), such as medical waste disposal, or the auditing of financials, with consequences if not adhered to.

The Role of Collateral and Mandated Services

Entities that possessed collateral or mandated services had a level power on their side but also had to deal with an added layer of complexity to their payment terms decisions since there was more bureaucracy to manage. To be able to cut services or delay shipments left both sides dealing with the potential ramifications from outside entities such as a State or Federal Regulations.

“We start with a position of power” because if they pay late, we can suspend service. (SNA Small, Health & Safety)

“Relationship determines their compliance.” (OM Small, Health & Safety)

Companies operating in web services, financial or healthcare industries often have collateral where performance obligations to customers could be delayed, outputs stopped or even reversed.

“In our agreements and contracts that you know, this is how we’re going to be billing you and if it’s not the case, then we ultimately have the right to not pay your employees.” (OM Micro, Payroll)

Those interviewed did highlight the fact that decisions to suspend service were not always easy. In the healthcare industry, for example, services mandated at a governmental level still left the customer with some power, as threats to deny service would not only hurt the customer but the patients requiring the essential care. As a result, the SME waiting on the payment often had to balance the competing pressures of compassion, compliance, people, and payments.

“In the nursing homes, they have to pay for laundry, food service, and even though our service is required to take care of the patient for diagnostics, we sometimes don’t get paid.” (SNA Large, Patient Care)

In other industries, similar difficult decisions had to be made by respondents when trying to assess whether there was sufficient collateral that could be used to facilitate timely payment, which could range from withholding shipments to whether the customer could survive without access to the specific skills and knowledge that the SME provided.

“Here’s an advantage that we hold over other people…I’m a technician, which means I can keep your machine running even over the phone. Nobody else can do that. So, if you order something from us and don’t pay me and your machine breaks down, I don’t know you.” (OM Small, Machine Repair)

“So, if we have like one of their regions isn’t paying like we can hold orders for like the other region and you know we’ll kind of kind of do it that way.” (SMA Medium, Craft Brewery)

“Give you an example: One of our customers, one of our huge customers’ orders anywhere from $5-6,000 worth of product at a time. Our terms are Net 15. They historically paid Net 45. What we did this past week is they ordered another run of products that is going to be about $5500. We held [the product]. For instance, if this company decided to go belly up and we’d ship them two shipments of product, that would be somewhere well over $10,000. And that would be hard to recover from for a small company.” (OM Small, Machine Repair)

However, those respondents in the service industry acknowledged that they were often at a disadvantage in terms of having collateral pressure to force customers to pay outstanding amounts due. Such entities usually lacked the ability to retract work, since most of their work was completed prior to invoicing and payments. Initial deposits, or requirements that the customer purchase the supplies for the job were often used to bridge the financing gap and remind clients of the tangibility and cost of the work completed.

“As a service industry – [we’ve] done all the work, you get the payments after everything is done. You’ve taken on all the expenses.” (OM Micro, Painting Services)

“50% deposit because I just want to make sure I am not chasing people for payment” after the work is completed. (OM Micro, Design Firm)

The presence of collateral or mandated services also allowed vendors to move into a more powerful economic position when negotiating payment terms, playing to the power dynamic often held by larger companies and banks.

“Have walked away from certain vendors who wanted to shorten payment terms.” (OM Small, Health & Safety)

“Our terms are non-negotiable, Net 30 days.” (SNA Small, Health & Safety)

Being paid and paid in a timely manner for any company is crucial to one’s cash flow due to the limited availability, accessibility, or usage of external financing, particularly lines of credit from financial institutions. In such contexts, trade credit remains a vital alternative to keeping the business going. Bussoli et al. (2022) previously highlighted this when focusing on the past financial crisis of 2008, when traditional credit channels tightened significantly.

Sources of Funding: Cash Flow, Credit Lines, & Alternative External Financing

Of the 39 US SMEs interviewed, it was possible to determine the main funding sources for 74% of them as shown in Table 4. For the remaining 26%, the respondents either did not know this information or chose to withhold it on grounds of confidentiality. Regarding the sources of cash that kept the businesses interviewed going, there was an almost even three-way distribution among them: some had a line of credit, others relied solely on their cash flow, and the remainder had access to alternative forms of external financial support. The external financial support, outside of the lines of credit from banks, encompassed having investors, some form of equity, or the support of a parent company.

Of the thirteen companies with ten or less employees (44% of companies interviewed), considered micro in terms of this paper’s size categorization, only one had a formal line of credit with a financial institution, and one had a private equity firm for support (with the remaining of the companies relying on cash flow, or unknown in their funding).

“Because we are a small business, we don’t like to have a tremendous amount of credit…we prefer to pay upfront.” (SNA Micro, Campground)

50% of the companies with 10-100 employees possessed a line of credit, though the degree of utilization varied between entities. For most respondents, the line of credit was seen as a “rainy-day” fund that would only be used in slow seasons, when large bills came due for taxes, or when emergencies arose that needed the extra cash.

“That’s kind of the boss’s approach on the business…keep our debt obligations as low as possible, $0 ideally and no credit cards either.” (SMA Small, Pet Waste Removal)

Regarding customer payments

“That’s our primary funding. We depend 100% on our customer payments. We do have a line of credit just in case… We don’t historically pull on it.” (SMA Small, Managed IT Services)

The majority of the medium and large sized companies (100+ employees, representing 30% of total respondents) interviewed had either a line of credit, investors, equity partners, or support through a parent company. However, none of them were willing to further discuss their comparative reliance on such funding versus cash flow to any further degree, usually directing any questions to press releases from the company itself. Thus, companies without wealthy owners or support from a parent company appeared more reliant on securing working capital through the use of a line of credit.

From the US interviews it was evident that “SMEs are more dependent on trade credit and bank credit, since they have limited access to financial markets” (Palacín-Sánchez et al., 2018, p. 1080).

“It’s like being in a rat race and especially it’s very challenging working for [a] privately owned [company] 'cause they don’t have the capital, and you know they just don’t have the infusion of cash.” (SNA Large, Patient Care)

“Receive money from customers faster, pay vendors slower” is always the goal. (OM Small, Wholesale Foods)

“You have more buying power [with trade credit], which lets you do larger jobs and gives you more opportunity for larger profit.” (OM Micro, Plumbing & Solar)

In interviews where the company was more dependent on the usage of payment terms as both a customer and supplier rather than a line of credit, respondents acknowledged that having a good working relationship with the credit giver or receiver was vital to the successful management of the company’s cash flow.

“I think having trade credits is good for building credit with other businesses and not necessarily the bank. Definitely try to keep accounts for that reason.” (OM Small, Restaurant)

This type of sentiment was commonly voiced by many of the US respondents and supports prior work that found despite “the propagation of transactional lending technologies, relationship lending is still considered to be one of the most potent technologies in terms of overcoming information problems, particularly that of adverse selection” (Cornée, 2017, p. 700).

The Influence of Relationship Dynamics

“Under relationship lending, the strength of the relationship between the lender and the borrower affects credit availability” (Murro & Peruzzi, 2021, p. 331).

For many SMEs, the business-to-business relationship between customer and supplier appeared to vary along a continuum - from warm, to informal, to strict formality. Interview respondents highlighted that building these relationships required time and effort, which in turn influenced discussions about payment terms, especially when the company faced cash shortages and a high volume of payables.

“Through our co-president building relationships with vendors over 30 years, he understands who he can lean on for sympathy and who he cannot.” (SMA Small, Research Equip.)

“It’s better to have a supplier in business, than longer payment terms for us” (when suppliers come to them about cash flow issues). (SNA Large, Technical Mfg.)

Although these business relationships were often developed outside of the finance department—through sales, operations, or the executives, accounting staff in some companies also frequently played a key role in bridging understanding and communication in ways that were both effective and mutually beneficial.

“People think accountants just kind of sit in the corner and do their journal entries and have a good time. But it really is a customer service industry and you have to learn how to balance it and build the relationships. And frankly, once you learn how to do that, it actually helps build the business even more and make you kind of more trustworthy, not only with your customers but with your vendors. And you can get more out of it.” (SMA Small, Managed IT Services)

Most respondents acknowledged that building and maintaining such relationships took considerable time, and these could be upset by changes in corporate structure and personnel. Not only that, but the need also to navigate cash flow issues through late payment had to be balanced against the potential for jeopardizing future access to trade credit.

“I’m like, well, show me. Show me everyone who owes [us] money. And it was a lot. It was about $400,000 and some of it was debt… like 2-3 years old. …Well, why don’t you let me go talk to these people and try to get our money back. And I was able to recoup probably about 85% of it and continue doing new business with them.” (SNA Small, Party Rentals)

The US respondents were clear in their support of the adage that ‘trust is earned, not given.’ This finding supports Collis et al. (2013, 2016) who found that “soft” relationship-based information was an important determinate of traded credit decisions of the US SMEs they interviewed. However, in contrast to the earlier literature, the findings presented here suggest that there has been a manifest change in how easily trust is given to new customers, and whether third-party sources of information are used within this determination. Until recently, D&B was viewed as an invaluable source of US business credit reporting information, allowing private businesses to establish their credit and show their money management choices through a formal setup (Collis et al., 2013). In recent years, this reliance appears to be changing, at least within the sample of 39 companies included in this paper:

“I’ve had suppliers call me up, you know, from a relationship perspective and say 'Hey…we’ve got major financial issues, we’re declaring bankruptcy, you’re going to see this break in the news and they’ve got just a sterling D&B report.” (SNA Large, Technical Mfg.)

“On the surface, I don’t think that it gives you all of the information you’re looking for. I think it’s kind of like as you know, good information, information in equals kind of, you know, bad information in equals bad information out. So, I take it with a grain of salt. In that that’s kind of like our first line of defense going look.” (OM Micro, Payroll)

For a recent new customer:

“We had a company in Raleigh that was on credit. They did not pay their bill; they went bankrupt and a month later they opened under a different name. Same ownership, but a different name. We refused to give them credit because it was the same people involved.” (OM Small, Machine Repair)

Consequently, US SMEs seem to be shifting away from relying on formal third-party credit rating information from D&B and other providers, as highlighted by Berger & Frame’s research into Small Business Credit Scoring (2007). Greater emphasis now rests on established business relationships and the trust that has been cultivated over time.

“Ultimately we don’t really care because Dunn [D&B] is kind of a joke.” (SMA Small, Managed IT Services)

When asking for anything when setting up a customer:

“I do not [do a credit check]. Not at all. And in fact, all I want is that first order. I just want an order, and I will get them product and I will trust that I will be able to collect the money because that 99.9% of the time, that’s what happens.” (OM Micro, Specialty Food)

“It kind of depends on how long of our relationship we’ve had with that vendor too. Typically, we’ll start off with smaller terms and then as we’ve worked with them for a couple of years, they kinda build that up, which is nice 'cause it helps us, you know, free up cash flow and then we can kinda plan.” (SMA Medium, Craft Brewery)

“Generally good with anybody – use credit application to sort out the shady.” (OM Small, Wholesale Foods)

Unfortunately, though, some respondents believed that trust could be exploited, as illustrated by one healthcare company interviewed:

“They [the owners] really pushed the terms” when paying suppliers. (SNA Large, Patient Care)

In certain cases, in addition to the relationships built, respondents acknowledged that trade credit references were still necessary before payment terms were granted. However, none of the 39 US companies interviewed provided any additional information to potential suppliers, and under no circumstances was financial data shared with them.

“We don’t fill out applications. We refuse to do that” (for vendors when getting payment terms). (SNA Large, Technical Mfg.)

Despite the time and effort invested in building strong relationships with their customers, companies were still vulnerable to the consequences of late payments—often triggering a ripple effect that impacted their own ability to meet obligations downstream.

Impacts and Implications of Late Payments

A significant majority of the companies interviewed would never willingly accept late customer payments—because disrupted cash flow can quickly resemble a Rube Goldberg machine, turning the straightforward flow of funds from Accounts Receivable to Accounts Payable into an unnecessarily extended, complex and inefficient process.

“We have never charged a late fee until now. We are just starting to implement that because of the problems we’ve had.” (ACC Medium, Sports Team)

While only one company interviewed purposefully delayed payments to build up their cash reserves, most respondents believed that when the cash was available, you paid your invoices when they came due. This could be seen as a direct connection to the power of the relationship built up over time between the two parties.

“When you tell somebody that you’re mailing them a check, you mail them a check. You don’t play games there; you’re just going to burn bridges and ruin a relationship.” (SMA Small, Research Equip.)

“Suppliers could put you on hold until you paid. It could be very stressful [and] yes, the owners were aware. You would continue to inform, provide the information, the risks, the repercussions of not being [paying vendors], but it is up to the owners.” (SNA Large, Patient Care)

As was discussed earlier in the findings, the power imbalance between the payor and the payee could create a highly uneven relationship—one in which the weaker company is left scrambling to make ends meet when extended payment terms or late payments themselves become the norm. Silva suggests while trade credit may be a way to keep a company flowing with cash, “high levels of trade credit increase operating risk due to payment delay or even default” (Silva, 2024, p. 1).

“You know it’s an extremely seasonal business. And if we have people with outstanding balances and we don’t collect right now like right now, we’re not seeing that money.” (SNA Small, Party Rentals)

When late payment occurred, the respondents discussed a number of different ways to “chase” payments: from incessant reminders, to stopping service, involving debt collection agencies, to the extreme decision of having liens placed on properties.

“When it’s past due, I send them a reminder. I believe you kill them with kindness and act really nice.” (ACC Medium, Sports Team)

“Debt collection seems like a racket.” (OM Micro, Painting Services)

“Collect through liens – hit and miss with limited power.” (OM Micro, Painting Services)

“It aggravates me when I cannot pay because if I don’t pay, usually means that my customers haven’t paid yet, which charges me [late fees from the vendor], but I should be charging the customers. But it’s hard enough just to get them to give you what they owe you, let al.one late fees.” (OM Micro, Plumbing & Solar)

Such activities were often seen as a last resort, especially where prior relationships had been good. However, respondents more heavily affected by late payments even had an employee or entire department dedicated to chasing down the money from their customers.

“It becomes difficult to retain people” when vendors get nasty." (SNA Large, Patient Care)

“We did not have a direct Accounts Payable phone line – that was deliberate.” (SNA Large, Patient Care)

As highlighted earlier, companies in the service industry faced a significant disadvantage when receiving and/or pursuing late payments, largely because they lacked the leverage of tangible collateral.

“I have very little in the way for protections.” (OM Micro, Painting Services)

It is “my responsibility to manage my receivables” as a service industry business. (OM Micro, Accounting Services)

For many respondents, late payments were viewed as more than simply a result of administrative or accounting issues or delays and instead seen as deliberate strategic power plays or a consequence of management decisions made elsewhere. Late payments consistently disrupted the flow of cash from customer to company to vendor, triggering a domino effect that left almost everyone feeling its effects. Despite efforts to manage these disruptions, the fallout often extended to the company’s ability to pay its own vendors on time.

Financial Transparency: Internal Practices and Public Disclosures

All respondents stated that their company would never prepare or provide any form of financial statements information to outside parties, except when required by financial institutions (to get, or maintain a line of credit), investors, or mandated auditors (based on the sector of business the company is operating within).

“We’re a privately held company. [We] won’t volunteer anything…[We] never show and tell.” (OM Micro, Medical Devices)

Respondents were prepared to give their financial statements to the bank, but not to customers or suppliers unless there was a specific request from a larger economic party that the company could not ignore.

“No, absolutely not – in fact, we make them beg [for copies of our financial statements].” (SNA Medium, Ice Machine Mfg.)

From a US perspective, such observations from respondents are unsurprising due to present accountability requirements for US private SMEs and this input supports the findings from earlier work by Collis et al. (2013 and 2016): “private firms in the US and Canada, for example, essentially face no financial reporting regulation. They are required to neither make their financial reports public nor have them audited” (Minnis & Shroff, 2017, p. 473).

Interestingly though, while adamant that financial transparency would not be considered to outside sources, several private companies interviewed had started to provide more visibility and communication around their financials for their employees. One company was employee owned and reviewed the high-level financials with the entire staff once a quarter. Since it was their money, the financial team wanted to make sure everyone felt as if they had skin in the game.

“I think we try to be as transparent as possible and as quickly as possible. With the management team especially so that they understand the business that they’re supposed to be running.” (SMA Small, Managed IT Services)

Discussion

The findings from the US interviews identified both similar and different themes to prior studies of trade credit decisions by SMEs.

As with Collis et al. (2013), a crucial contingent factor was the relative size and economic power of customer and supplier, with a “David versus Goliath” situation often arising at the US firms interviewed, due to the fact that “granting trade credit may not be a choice for ‘small’ suppliers. Firms with strong economic power could impose payment terms to maximize the availability of internal financial resources and decide whether and to whom they delay payment. As many of the US SMEs interviewed had limited market power, the extension of trade credit to customers simply reflected their relatively limited bargaining power, especially when dealing with large customers. As such, longer payment durations indicate that SMEs appear to adjust to large customers’ requirements” (Lefebvre, 2023, p. 1316).

In addition, an apparent cycle of delayed payments highlights a broader issue for US private SMEs: limited financial transparency. With limited visibility about the financial pressures and practices of one’s trading partners, companies are left reacting rather than planning, further weakening trust and stability across the supply chain that could be mitigated by the implementation of mandatory reporting regulations for all US private SMEs (Minnis & Shroff, 2017).

A comparative analysis of the relative benefits and limitations between the lack of financial transparency within the US against the greater accounting requirements for SMEs in other jurisdictions is beyond the scope of this paper, due to the extenuating circumstances of social, political, and economic forces within each country’s borders. However, the international literature on this topic within the UK and EU provides clear analysis of the disparities between accounting regulations and the lack thereof for private SMEs (Allee & Yohn, 2009; Collis et al., 2016; McGuinness & Hogan, 2014; Minnis & Shroff, 2017; McNamara et al., 2019, and Palacín-Sánchez et al., 2021). Such accounting requirements impose compliance costs for the preparing company but can serve to improve the public availability and overall quality of business-to-business information, thereby reducing the reliance on third-party sources of credit rating information [@504305;(Minnis & Shroff, 2017).

In summary, the relative lack and use of “hard” financial statements information within the payment terms decisions of US SMEs stands in direct contrast to its importance for UK and EU SMEs (see for example, Collis et al., 2013, 2016; Minnis & Shroff, 2017) but helps to explain the relative reliance and consequences of “soft” relationship information within the US. Should the accounting regulatory framework for US private companies ever change, it would be interesting to see whether mandatory public disclosure of financial accounting information disrupts establish patterns of behaviour with regard to the determination of payment terms decisions within the US.

This study expands the current understanding of the critical role payment credit terms play in the financial setup and management of private SMEs in the US. The findings offer meaningful contributions to the following bodies of literature:

-

Access to finance: Emphasizing payment credit terms as a vital long-term financing option for SMEs, serving as an alternative to traditional funding sources.

-

Business-to-business relationships: Enhancing understanding of payment term negotiations, practices, and limitations within customer-supplier dynamics.

-

Financial reporting regulations and requirements: Addressing gaps in empirical evidence in the context of US private SMEs who often operate without reporting requirements, changing the landscape between hard and soft information available.

The research questions addressed in this paper underpin and contribute to all these significant findings. Within the US interviews, “soft” relationship information was the most influential factor within the payment terms credit decisions at most companies, but this was moderated by the presence of various contingent factors, including: the relative size and economic power of the parties; presence of collateral and mandated services, and the reliance on trade credit as a source of financing.

Building on the prior literature, the most significant contingent factor identified was the variation in regulation and financial reporting requirements for SMES between the US and other international regions—especially the UK and EU— which significantly shaped respondents answers, a point emphasized by Minnis and Shroff (2017) in their analysis of US private SMEs. Many small US SMEs do not produce periodic financial statements, and for those that do, few would be willing to provide them in order to secure trade credit from a supplier, as this quote neatly demonstrates:

“Who’s going to give you their financial statement? I don’t think it’s going to happen. I mean they’re [banks] going to get your financial statements, but business-to-business – I’ve never heard of such a thing.” (OM Micro, Medical Devices)

Thus, the payment terms decisions by US SMEs included in this paper had to be made using other types and sources of information due to the complete absence of publicly available financial statement information. Thus, it was less a choice but an adaptation to rely on less formal non-accounting information. As a result, relationships became much more important in such decisions.

In contrast to prior studies, Collis et al. (2013, 2016) observed a growing reliance on credit scoring in the US; however, our findings suggest the opposite – a decline in credit scoring’s prominence, supplanted by the increased importance of relationships. This shift may be attributed to changes in bank loan availability and the lasting impact of the 2008 economic crisis (as highlighted by Bussoli et al., 2022; Casey & O’Toole, 2014; DeYoung et al., 2015; and Pattnaik et al., 2020).

Conclusion

SMEs throughout the world demonstrate some degree of reliance on payment credit terms to complement their access to other funding sources – a theme repeatedly highlighted in this study – but the factors and information that influence trade credit decisions vary widely across jurisdictions, especially in the US due to a lack of publicly available accounting information about SMEs.

It is important to recognize the inherent limitations that may affect the validity of this work. The main limitation of the research is the constraining nature of the data, with a restricted number of private US SMEs interviewed. This does not detract from the objective which was the generation of understanding of the importance of payment terms and trade credit and its complementarity towards available sources of funding. However, it would be desirable to follow up the work with more extensive, in-depth surveys across company sizes and industries using the concepts and themes generated in this work to extend and refine the findings, especially to enhance understanding of the contingent factors that may influence trade credit decisions in specific industries.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank W.J. Churchill for his dedication and contribution towards maintaining the integrity of the data.