INTRODUCTION

In the past, AACSB accredited Colleges and Schools of Business were chastised for lacking practical learning experiences (Porter & McKibbin, 1988). In response to these valid criticisms, many business programs introduced experiential learning activities embedded in existing courses or by creating new courses. Among the many types of experiential learning activities is field-based student consulting. The field-based consulting projects were made popular with the Small Business Institute program sponsored by the US Small Business Administration from 1973 to 1996 (Bechtold et al., 2019, 2022; Cook et al., 2013; Heriot & Campbell, 2002).

This article observes the use of field-based student consulting projects (FBSC) at a College of Business from 2006 to 2021. Students taking Small Business Management were required to complete a field-based student consulting project for a small business in their community. The project was one of several forms of assessment in the course.

This study uses a case research design to observe the evolution of the SBI program at this university. A case study allows the researcher to explore a phenomenon in much greater detail than other research designs. The case research design is a qualitative research method (Yin, 1994). Using a case method approach, we were able to observe the use of student consulting over a fifteen-year period. Therefore, we adopted a research method described by Audet and d’Amboise (1998): “combin[ing] rigor, flexibility and structure without unduly restricting our research endeavor” (Audet & d’Amboise, 1998, p. 4 of 10). Qualitative research designs have previously been used to describe field-based student consulting programs (e.g., Bechtold et al., 2022; Cook & Campbell, 2022).

This study contributes to our understanding of field-based consulting by observing a program at one university over an extended period of time. Previous studies have observed field-based consulting over shorter periods of time (Heriot & Campbell, 2004) rather than using a longitudinal approach. In addition, the present study demonstrates that the use of field-based student consulting (FBSC) is not without challenges that might jeopardize the viability of this approach to active learning.

The second section briefly reviews the extant literature related to field-based consulting. Our review, by necessity, evaluates the published literature on the Small Business Institute (SBI) program, which represents the most widely cited application of field-based student consulting. The third section presents information from our case study. We discuss the case study’s results in section four and conclude the article in section five.

LITERATURE REVIEW

A rather extensive body of knowledge exists about entrepreneurship education and small business management (e.g., Gorman et al., 1997; Solomon et al., 1998; Vesper & Gartner, 1997). However, this review will focus on field-based student consulting and the Small Business Institute (SBI). The Small Business Institute has focused on providing FBSC since its inception in 1973. An SBI program introduces action learning into the entrepreneurial pedagogy. Auster and Wylie explain that the “focus of active learning is on developing not only students’ knowledge but also their skills and abilities…” (Auster & Wylie, 2006, p. 334). Scholars have considered many facets of the SBI program and FBSC in parallel with the use of this pedagogy to assist small firms.

Studies focused on the Small Business Institute program date back over 25 years (e.g., See Brennan, 1995; Dietert et al., 1994; Hatton & Ruhland, 1994; Schindler & Stockstill, 1995; and Watts & Jackson, 1994). These studies have focused on several aspects of field-based student consulting, including, but not limited to, benefits to students, clients, and faculty. Other studies have identified other issues, such as the loss of federal funding when SBI was a Small Business Administration (SBA) program (Brennan, Hoffman, and Vishwanathan (1997), and broader issues, such as networking opportunities and interaction with the local community (Lacho & Bradley, 2010). More recent research has continued to address field-based student consulting as part of an SBI program (e.g., Cook et al., 2013; Cook & Belliveau, 2006; Cook & Campbell, 2022). As noted, most of the studies focus on the ability of the SBI program to provide clients with a viable consulting job, student-educational benefits, or impact on the community.

For many schools, a primary impetus for starting an SBI program was the potential benefits for students’ learning experience. The benefits of field-based consulting, specifically as part of a Small Business Institute program, have been identified by several research studies. We highlight some of these studies but do not suggest that this review of the benefits of field-based consulting is complete. The literature (Brennan, 1995; Hedberg & Brennan, 1996; and Borstadt & Byron, 1993) provides considerable evidence that SBI programs are of educational value to students. In addition, recent evaluations of business schools have called for “a stronger practicum and projection emphasis in both curriculum and coursework” (Lyman, 1997). The SBI program represents just such a practical approach to learning and applying business concepts. In 2006, Ames (2006) emphasized the benefit of student consulting due to the dynamic group activities of the students participating in the program. Students must work with one another to complete complex tasks to assist their clients.

A study by Heriot, Cook, Matthews, and Simpson (2007) demonstrated the impact that FBSC can have on students. They concluded that by participating in an SBI program, “Rather than passively receiving information, students must do something tangible that someone other than the instructor will observe. Under the professor’s guidance, students evaluate a real-world business problem and must decide upon a solution” (Heriot et al., 2007, p. 434).

A more recent study by Hoffman and Bechtold (2018) argues that the SBI program is uniquely designed to overcome concerns about declining student performance and lack of critical thinking and analytical skills. The field-based consulting projects that the students complete are designed to be experiential in their very nature. SBI projects require students to develop tacit knowledge to complete consulting projects that contrast significantly from the explicit knowledge that traditional approaches to education develop through participation in class lectures and reading textbooks.

Additional studies have examined other benefits of field-based consulting, such as negotiation and networking skills (Lacho & Bradley, 2010) and community development opportunities (Lacho & Bradley, 2010).

Most previous research has highlighted the benefits of field-based student consulting to the students and the client. However, field-based student consulting can be beneficial to faculty as well. A study by Bradley (2003) emphasized the economic development aspects of completed field-based student consulting projects. A more recent study by Lacho and Bradley (2010) emphasized that faculty leading the FBSC program benefited as they worked closely with members of the community. Their study highlighted not only the value of negotiation and networking to students but also the community development opportunities for faculty.

The study by Lacho and Bradley is better appreciated now, even more so than in 2010, because societal impact was not a metric that AACSB or other accrediting agencies emphasized (AACSB introduced societal impact as a metric when the 2020 AACSB Standards replaced the 2013 Standards), but anything tied to economic development is clearly an example of societal impact. The most recent study uses a qualitative case study approach to highlight the benefits of field-based consulting to faculty as well as students, clients, and other stakeholders (Bechtold et al., 2022).

Most of the extant literature describes field-based consulting in glowing terms. However, at least three studies focused on a difficult period for programs that used field-based student consulting in the 1980s and 1990s. The research of Vishwanathan, Hoffman, and Brennan (1996) and Brennan, Hoffman, and Vishwanathan (1996, 1997) addressed the loss of federal funding by SBI programs when it was a program funded by the SBA. Their work gathered information from SBI Directors just prior to the cessation of federal funding for the SBI program and subsequently after funding was eliminated. Their initial research (1996) predicted that many schools would eliminate the SBI program due to the loss of federal funding. The second study Brennan et al., 1997 revealed that almost 80 percent of the common respondents continued to operate SBI programs. However, only sixty-two percent said they planned to continue the SBI program. Of those who planned to discontinue their SBI program, 79 percent said lack of funding was the primary reason for discontinuing their SBI programs. Thus, one might conclude that starting a new SBI program would be a difficult, if not impossible, undertaking given the attitudes of SBI Directors in the studies.

Contrary to this concern is more recent research that suggests the viability of creating a new SBI program (Heriot & Campbell, 2002, 2004). It is important to provide context to the Brennan et al., 1996; and Brennan et al., 1997 studies. At that time, the SBA had discontinued funding the Small Business Institute program. That federal program paid participating universities to complete field-based student consulting projects within each fiscal year. Fast forward to the present day, field-based student consulting is used at many universities, and federal funding is no longer relevant.

A more recent study addressed concerns about the relationship between field-based student consulting and accrediting agencies like AACSB International. Bechtold, Hoffman, and Murphy’s study (2019) asks the question, “Can the SBI Program Survive”? The original emphasis of AACSB on scholarship represented a threat to SBI that had less tangible and quantifiable benefits. However, the enhancement of the 2013 AACSB Standards with the 2020 AACSB Standards represented a light at the end of the tunnel as impact, innovation, and engagement were introduced as desirable metrics (AACSB International, 2013, 2020). The standard now states, "The school demonstrates positive societal impact through internal and external initiatives and activities, consistent with the school’s mission, strategies, and expected outcomes (AACSB International, 2020, p. 55).

In summary, the published research on SBI and field-based student consulting has focused on the benefits of SBI programs to either the student (Brennan, 1995), the faculty member (Bechtold et al., 2022), the client (Madison et al., 1998), as a planning tool (Hoffman et al., 2016), as well as the impact of losing federal funds (Brennan et al., 1996). Despite a fairly large number of articles on SBI and field-based student consulting, very few published studies investigated the creation, management, and sustained use of field-based student consulting over an extended period. More importantly, the extant literature emphasizes the positive aspects of field-based student consulting. This study addresses the challenges of administering a field-based consulting program. We do not question the viability of field-based student consulting but rather consider what might lead to the cancellation of an FBSC program in response to changing conditions. By addressing the potential for problems with an overall program, this article fills a gap in the received literature.

THE QUALITATIVE CASE RESEARCH STUDY

The School

The focal point of this case study is a small urban university in a southern state. The university is in a city with approximately 200,000 people. Figure 1 below summarizes information about the city, which has a combined governmental structure with the county in which it is located.

As of September 1, 2023, the university had approximately 7,300 students, with 900 students enrolled in the Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) program housed in the College of Business. The BBA program offers majors in Accounting, Finance, General Business, Management, Marketing, and MISM. The College has three graduate programs. They have a traditional MBA, an online MBA, and a Master of Science in Organizational Leadership. Lastly, the undergraduate management major has three concentrations in human resources, entrepreneurship, and international business, which share two required courses with one of the six academic majors. The College also has a School of Computer Science, which largely operates as an independent academic unit.

In 2006, the business program offered one course with entrepreneurial content, Small Business Management. It was a required course for management students and a business elective for other students. FBSC became a significant part of the Small Business Management course in the Fall semester of 2006. In addition, a second course was approved but had yet to be offered. It was entitled Entrepreneurship and New Venture Creation. This course was eventually split into two new courses: Introduction to Entrepreneurship and New Venture Creation. Sometime around 2010, a fourth course was created that was designed to focus on only FBSC (small business consulting), but this course was never offered due to faculty resource constraints.

Size and Scope

FBSC was provided each academic year but was not required in all sections of the course. In 2014, a new faculty member did not use FBSC in sections of the course they taught. FBSC was administered each academic year, but it was not offered in two calendar years, 2013 and 2015, due to the peculiarities of an academic year versus a calendar year. However, this did not create an administrative problem since other outcomes were used for the purposes of assessment in the Bachelor of Business Administration degree (BBA).

Getting Started

The decision to use FBSC is both an opportunity and a challenge. Requiring students to work with a small business is experiential, and one of the few chances college students have to put into practice the many things they have learned in their academic program. On the other hand, from the instructor’s point of view, supervising student teams can be viewed as a daunting challenge. At the time the decision was made to adopt the FBSC pedagogy the situation was not complicated. The instructor joined the faculty as the first endowed chair in entrepreneurship. They were assigned to teach five undergraduate courses each year and one MBA course. Additional responsibilities included the typical research and service duties expected of faculty at an AACSB-accredited college of business. The teaching load was only one factor that set the stage for whether FBSC would be introduced into the curriculum at the College.

An instructor contemplating using the FBSC pedagogy must consider several factors. Their teaching load is an obvious starting point. The individual who used FBSC was an experienced faculty member with a publication record and experience administering and starting Small Business Institute programs dating back to the era when the SBA funded SBI.

Even if a faculty member is accustomed to being assigned a typical teaching load in an AACSB-accredited business program, the use of FBSC is time-consuming. Supervising 7 or 8 projects in each section of a course using FBSC is not to be taken lightly. So, one must consider the time required to monitor the teams beyond simply the number of assigned courses. There is also an issue about course content. How much of the course is built around the consulting assignment? Teaching a course in small business management requires a variety of topics to be covered. A faculty member might cover 12 or more chapters per semester with writing assignments included in the overall scope of work for students.

A third factor involves the faculty member’s other obligations. Faculty members are generally expected to teach, provide service, and conduct research in peer-reviewed journals to remain qualified at an AACSB-accredited business program. Thus, research expectations need to be considered before FBSC is adopted. A final factor is related to the teaching load. That factor is the relative ratio of undergraduate courses and graduate courses. As noted previously, in the Fall semester of 2006, the faculty member was assigned five undergraduate courses and one graduate course per 10-month academic year.

The aforementioned factors are major issues one must address before moving forward with FBSC. They reflect some, but not all, of the factors one might want to consider before adopting FBSC. Thus, each person contemplating FBSC will need to consider their own unique circumstances as a college faculty member faced with any number of expectations in their personal and professional life.

Execution

Once a decision has been made to use FBSC, one must focus on how it will be accomplished. Some business schools have gone so far as to create a program that organizes projects on a regular basis. This decision is not really an issue in the day-to-day administration of the course and the projects, but it does set the stage for how to recruit both students and participating companies. The FBSC projects were not administered in the traditional way most SBI projects are completed by student teams (See Cook & Belliveau, 2006 for details). The projects were set up by the student teams and were limited to a single functional area in the business. Thus, for example, students would not assist with writing a business plan or even a complete marketing plan but would instead work on what we described as a micro project (Heriot et al., 2008). Traditionally, a typical FBSC project is set up by the instructor on behalf of the team of students (Cook & Belliveau, 2006). This work is done before the semester begins and can be very time-consuming as it is often a hit-or-miss process to identify and recruit small businesses.

Between 2006 and 2021, seven hundred eighty students were enrolled in the sections of small business management that included FBSC. Table 1 provides enrollment numbers for the sections of small business management that included FBSC between 2006 and 2021. The course in which FBSC was administered was scheduled at least once per academic year. As noted, it was not offered each calendar year due to the peculiarities of academic years versus calendar years in higher education.

The use of field-based cases can be accomplished in any number of ways. At this university, the students were required to complete a project during the semester concurrently with the other graded requirements of the course. A small business management textbook was used to discuss different facets of managing a small business. Twelve of 21 chapters were covered in the textbook. So, an effort had to be made to include class time for discussing each chapter and discussing projects. Initially, the increased use of online communication and virtual meetings actually helped improve this process. Time does not have to be used during class to meet with student teams. On the other hand, online instruction makes it harder for teams to work together or for the instructor to monitor teams in real time (e.g., meeting in class 2 or 3 times per week).

There were a variety of types of FBSC projects that students completed. Figure 2 broadly summarizes information about the clients and their companies, students, and the types of FBSC projects that were completed between 2006 and 2021.

Finding Balance

Since 2006, the initial circumstances changed dramatically, impacting the use of FBSC in the small business management course. These circumstances increased the duties of the instructor who supervised the FBSC projects. As a result, it became increasingly difficult to keep up with multiple student consulting projects. In a section of the course with 30 – 40 students, there might be as many as 20 ongoing projects because of the use of the micro-consulting approach (Heriot et al., 2008). Figure 3 highlights critical events that changed the initial circumstances and the associated actions or decisions directly related to each critical event between 2006 and 2022.

While each event had an impact, four of the eight critical events dramatically impacted the use of FBSC projects in the course Small Business Management between 2006 and 2021. These challenging events are highlighted in bold in the left column of Figure 2. As noted in the section about getting started, research and service obligations are essential considerations when deciding to use FBSC. The new standards of AACSB have increased the need for published research. Within the scope of this case study, the additional responsibilities of one of the authors took time away that was previously devoted to supervising teams. The additional duties included, but were not limited to, creating a new undergraduate concentration in entrepreneurship, serving as the course lead for Entrepreneurship, a required course in the College’s online MBA program, and supervising a business plan competition created in 2011.

The Impact of Critical Events

Figure 3 highlights what can best be described as the perfect storm of critical events listed in Figure 3 above. Out of the eight critical events highlighted in Figure 3, the four bold-faced in Figure 3 put increasing pressure on using the FBSC. In this subsection, we consider each of them individually.

In 2011, the College joined a consortium of five other AACSB-accredited colleges to offer an online MBA. This MBA program was in addition to the traditional one offered on campus. The online MBA program included a required Entrepreneurship course. In order to ensure as much overlap between the on-campus MBA and the online MBA, a required entrepreneurship course was added to the curriculum of the on-campus MBA program. The instructor of the small business course was selected as the course lead for the entrepreneurship course in both graduate programs. The graduate entrepreneurship course was far more rigorous than the undergraduate courses that were taught each year. As a result it created additional work that had to be done to lead the MBA entrepreneurship course faculty and make changes based on the assessment results. In addition, as course lead, the instructor of the course was assigned to teach between 2 and 3 sections of both the MBA and the online MBA entrepreneurship course each year. Thus, between 2006 and 2022, the faculty member went from teaching one graduate class per year to teaching as many as three graduate classes per year.

Online instruction has become a reality for many universities in the United States. The small business course was scheduled for both online and face-to-face instruction around 2008. This was not initially a problem because another faculty member taught one of the two sections scheduled each academic year. However, this individual left to accept a faculty position at another university. The new faculty member who filled the vacancy was not assigned to teach the small business course online or in the classroom. Thus, there was a need for all sections of small business management to be taught by the same instructor. Online courses can be incredibly convenient for students. However, they are far more time-consuming to teach because of the technology required and different interactions with the students. The asynchronous mode of delivery meant the instructor had to be available far more often to work with students or address questions or concerns than would happen if the class was offered in a predictable two or three-day-a-week schedule. The adoption of online delivery was further complicated because all instructors in the College of Business were required to complete Quality Matters training and have their online courses certified by Quality Matters.

A concentration in entrepreneurship was proposed to the College and later the university curriculum committee and was approved effective Fall 2016. The concentration required the creation of a new introductory course in entrepreneurship. In addition, it had to be administered, which represented more time spent out of the classroom. The new concentration officially became an academic option in the Fall of 2018.

The COVID-19 pandemic was not something even the most brilliant scientists were able to predict. Everything about higher education was turned upside down by the most fatal pandemic since the Spanish Flu of 1919. Not surprisingly, COVID-19 had an unprecedented impact on the use of the FBSC pedagogy at the university and its College of Business.

In the middle of the Spring Semester 2020, all classes were converted from face-to-face to online instruction. This transition was incredibly difficult because it completely changed the dynamics of the section of the course using FBSC teams because it was intended to be taught face-to-face. Students were largely restricted to their homes, and their clients’ businesses were either closed or the students and the business owners were not comfortable meeting with one another.

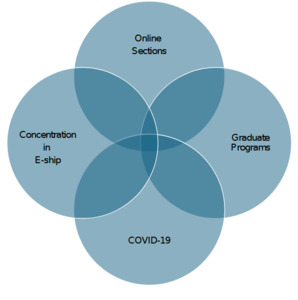

Each of these four critical events was not overly difficult to overcome individually. However, their collective impact was tremendous. Figure 4 below uses a visual image to capture the perfect storm of these four events. The intersection of these four events highlights the situation that evolved due to these external factors. The instructor who used FBSC was the only entrepreneurship faculty member in the entire College of Business. There was no organizational slack (Bourgeois, III, 1981) available to absorb the collective impact of these four critical events, which led to an untenable situation (Chen and Kesner, 1997).

Future of the program

Of the eight small business management course sections scheduled between 2019 and 2022, only two were offered in a classroom. Enrollments in the course remained high between 2006 and 2022, but there was often a large variation between sections, especially when the course was offered at night for the benefit of non-traditional students as opposed to being offered during the day or online. Online course sections were very large.

Following the spring semester of 2022, a decision was made to discontinue the use of FBSC projects in the small business management course, which is now called Entrepreneurial Small Business. The four critical events highlighted previously collectively made it nearly impossible to effectively monitor as many as 15 two-student teams each time the course was scheduled in both the fall and the spring semesters.

An obvious solution might have been to hire more faculty or re-assign faculty to the entrepreneurship program, but the university’s enrollments were flat or declining. Thus, the College was not authorized to hire new faculty to teach the entrepreneurship courses or take over the primary instructor’s graduate course assignments. In addition, the College struggled to hire part-time faculty due to incredibly low salaries for instructors, which were often times less than $3,000 per course for an individual with an MBA, M. Acc., or MS degree.

Another option might have been to create a separate class devoted entirely to FBSC. Cook and Belliveau (2006) demonstrated the viability of such an approach. Unfortunately, adding a new course to the schedule was not viable in the situation faced at the College. Creating a new course would still require an additional person to teach it. As noted previously, such faculty resources were simply not available, especially for the salary paid to part-time faculty or the availability of a new faculty member.

DISCUSSION

In 2006, a FBSC program was created as much due to familiarity with FBSC as it was any other reason. The instructor for the course supervised SBI projects while completing his doctorate. He had used FBSC at three other universities. To some extent, stubbornness and a commitment to SBI and FBSC were prominent reasons it continued to be used despite the impact of the four critical events discussed previously.

Throughout the timeline in the case study, the student consulting projects were administered in a simple fashion. The use of micro consulting projects led by the students was unique to the use of FBSC. It was not organized the way Cook and Belliveau (2006) explain how to administer typical field-based student consulting projects. Nevertheless, it accomplished many of the positive outcomes associated with FBSC without fully embracing the way others might adopt the use of FBSC.

Field-based student consulting (FBSC) is a proven experiential activity. The decision to use FBSC is both rewarding and challenging. Requiring students to work with a small business is experiential and one of the few chances college students have to put into practice the many things they have learned in their academic program. On the other hand, from the point of view of the instructor, it can be viewed as a daunting endeavor. It requires a considerable amount of effort to implement it.

Lessons Learned from this Study

The experiences of the College of Business in this study provide some lessons learned for others who are thinking of introducing FBSC or to existing programs that might face the same challenges faced by this College’s FBSC program from 2016 – 2022. Several issues need to be considered before adopting FBSC. Keeping up with multiple student projects in each course section is time-consuming. So, one must consider the time required to monitor the teams. There is also an issue about course content. How much of the course is built around the consulting assignment? A third issue is associated with the other duties an instructor might have. Someone at an AACSB-accredited business program is typically required to publish in peer-reviewed journals. How does the use of FBSC affect one’s ability to publish? A fourth issue is the mode of delivery. Are students taking the class in person or online? These are just four issues that must considered. They are not an exhaustive list of issues. In fact, each person contemplating FBSC will need to consider their own unique circumstances as a business faculty member faced with any number of expectations in their personal and professional life.

As the program evolves, the duties of faculty members responsible for FBSC will need to be considered. The program’s evolution in this study represented the perfect storm of external events that could not be overcome due to resource constraints, specifically, a lack of other faculty available to take over the FBSC course or teach other courses in the Concentration in Entrepreneurship. These resource constraints might not be an issue at larger, better-funded colleges or colleges with large endowments considering creating an FBSC program. For those programs, this lesson learned is clearly not applicable. However, for colleges with fewer resources, particularly fewer faculty members, the experiences of this College are worth noting. As is true in any case study, much of the value comes from the ability to learn vicariously from the past actions of others, thereby avoiding those same pitfalls.

LIMITATIONS

The case research design used in this study limits one’s ability to generalize to other FBSC programs or to the use of the FBSC pedagogy. However, that was not the purpose of this study. The case method was carefully chosen to capture more details about what happened than could be gathered using a more traditional quantitative research design. To that extent, this study was similar to other published studies (e.g., Bechtold et al., 2022; Cook & Campbell, 2022). Furthermore, this study described the creation and administration of an FBSC program at an AACSB-accredited university over 16 years.

CONCLUSION

This study presents a chronological view of the use of FBSC at an AACSB-accredited college. It provides a detailed view of the experiences of one instructor who assigned student consulting teams over a 15-year period. The study was not shared as an example of best practices but rather as a means for other business faculty to learn more about the use of FBSC over an extended period of time.

FBSC can be a wonderful experience for students, faculty, and small business owners with the support of the administration, the passion of the instructor, and some effective preparation. Student consulting is a way to introduce action learning (Heriot et al., 2007) into the curriculum of business schools using a proven method that allows students to use their newly developed business skills. Consulting projects are a unique form of active learning (Heriot et al., 2008). The projects require interaction between a team of students and a business owner faced with a real problem or issue that needs to be resolved. The present study is important because it provides longitudinal evidence of the creation, administration, and sustainability of FBSC over a 15-year period of time.

From 2006-2022, 780 students at the university in this case study completed field-based consulting projects on behalf of 350 small businesses. The students engaged in active learning, and the small companies received consulting supervised by an instructor at no cost to the business. It is our hope that this study can inform college faculty and administrators who might have an interest in FBSC. FBSC is a unique pedagogy. There is strong evidence that it represents a great way for students to learn and provides a great service to members of the community. However, it is not for every instructor or every business program. The adoption of FBSC cannot be taken lightly. It must be a good fit within the overall business program’s structure, culture, and staffing. In some respects, deciding to use FBSC is the easy part. Sustaining FBSC is an entirely different matter. As the results and the timeline in this study show, unforeseen circumstances might lead to a situation when FBSC is no longer viable, given the reality faced by the individual(s) administering FBSC in their courses.