Finding the right employees in small businesses may be more important than in larger businesses since smaller businesses have fewer resources (human and financial) to recruit and train new employees. For example, a recent study of small businesses by Babson College and Goldman Sachs found that while small businesses lead in economic growth, workforce investment, and commitment to workforce training and wage growth, they have resource constraints (Babson College, 2019). Small business leaders may make hiring decisions based on low-cost indicators such as one’s education, experience, grades in school, intelligence tests, and/or personality tests. They may also consider a job candidate’s person-organization fit by the interviewers’ first impressions and whether they perceive they have chemistry with the candidate (e.g., Abraham et al., 2021). During the selection process, it is important to identify top talent because talented, engaged employees contribute significantly to a small business’ reputation, legitimacy, and success. Yet it is equally important to hire in ways that increase diversity and do not discriminate based on characteristics such as gender or race.

Two personality traits that could be important in making these determinations are core self-evaluations and psychological entitlement. Core self-evaluations (CSE) are a broad, higher order construct that marries self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, emotional stability, and locus of control (Judge et al., 1998, 2002). CSE relates to a person’s assessment of their effectiveness, worthiness, and capability (Judge et al., 2003). Psychological entitlement is a personality trait in which one believes he or she is entitled to more than others and is characterized by exaggerated expectations, perceptions of specialness, and deservingness (Grubbs & Exline, 2016). It is the view of oneself as specia6l or privileged (Campbell et al., 2004). While numerous studies have identified the outcomes of these constructs (e.g., Campbell et al., 2004; Judge, 2009; Judge & Bono, 2001), fewer have examined demographic inputs, such as gender and employment status or values such as self-enhancement (c.f., Judge et al., 2009; Li et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2014). The present study contributes to existing literature by analyzing the literature, proposing hypotheses, and testing the hypotheses on a dyadic sample of higher-level university business undergraduates. Given that college graduates are often desirable to employers, our population may be relevant to small business practitioners who consider various personality and behavioral traits in the hiring process. These issues may also be important to readers of the Small Business Institute Journal (SBIJ), as a recent study of articles published in SBIJ found that issues of human resources, gender, and diversity are somewhat underrepresented when compared with strategic, small business education, and entrepreneurial topics (Mesa & Holt, 2021). Furthermore, Dunn, Short, and Liang (2008) found that small businesses with 11 or more employees consider human resource management more important than their smaller counterparts, so leaders in firms of this size may benefit from assistance and insights. In addition to recommendations on tailoring recruitment processes to optimize candidate selection, study results have implications for pedagogy, which can be defined as evidence-based insights into developing skills and attitudes associated with better outcomes for employment, job satisfaction, and income (Dondi et al., 2021).

Core Self-Evaluations (CSE)

Judge and colleagues define core self-evaluations (CSEs) as individuals’ “basic evaluations of themselves and of their success in and control over their life” (Judge et al., 2009, p. 744). CSEs reveal an individual’s perceptions of his or her competence, capabilities and “a general sense that life will turn out well for oneself” (Judge, 2009, p. 58). CSEs combine self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, emotional stability (low neuroticism) and locus of control (Judge et al., 1998, 2002). Research into this higher-order construct shows greater predictive validity of important work outcomes such as job performance, job satisfaction, stress, life satisfaction, and work motivation than the separate constructs that comprise it (Judge, 2009).

CSE theory (Judge et al., 1997) posits that individuals’ views of their own lives drive their intentions and behaviors. Previous research supports the use of CSEs in hiring because people with higher CSEs have better job outcomes. For example, higher CSE levels are associated with higher job satisfaction and improved job performance (Judge & Bono, 2001), higher conflict management quality (Siu et al., 2008), greater productivity and task motivation (Erez & Judge, 2001), and more work success measured as both task behavior and performance ratings (Erez & Judge, 2001; Judge, 2009). Higher CSEs are also related to greater happiness and life satisfaction (Piccolo et al., 2005), higher emotional intelligence (Sun et al., 2014), fewer perceived stressors, less strain after controlling for stressors, less avoidance coping, and higher organization-based self-esteem (Pierce & Gardner, 2009). Physically attractive people or individuals who have high general mental abilities also have higher CSEs (Judge, 2009; Judge et al., 2009). CSEs also correspond positively with income and educational attainment and negatively with financial stress (Judge et al., 2009).

The effect of CSEs seems especially useful in helping individuals take advantage or leverage other positive situations or environments. Individuals with various physical, income, or cognitive advantages (or privileges) may have higher CSEs. For instance, higher socioeconomic status, educational attainment, and strong academic performance in adolescence and young adulthood corresponds to higher income later in life for those with high CSEs (Judge & Hurst, 2007). For those with lower CSEs, these early life advantages made little impact (Judge & Hurst, 2007 In other words, it appears that those with early advantages in life may benefit as those advantages correspond to their self-evaluations later in life.

In one metanalytic study (Gang et al., 2022), females had slightly lower core self-evaluation levels than males. Gang et al. (2022) posited that women’s assessments about their abilities and competencies might be influenced by their cultures, yet their research found only trivial (though statistically significant) gender differences in CSE in the United States and Europe and no differences in Asian or Australian samples. They drew from evolutionary theory (Buss & Schmitt, 1993) to posit that males and females have different evolutionary requirements and pressures and social role theory (Eagly & Wood, 1999) to posit how the traditional male and female division of labor relates to societal expectations, norms, and sex-differentiated behaviors. Women have historically been considered nurturers while men have been workers or warriors, so these roles may have had an impact on male and female personality traits and beliefs (Gang et al., 2022).

In another study of first-year university students, researchers have found that white students had higher levels of CSEs than other ethnic groups (Griggs & Crawford, 2019). Researchers have suggested that the impact of gender and race on CSE levels may be due to being in underrepresented groups or groups that have historically faced discrimination (Griggs & Crawford, 2019). Given the self-esteem component of the CSE construct, one could posit similarly with Tajfel and Turner (1979) that social identity as a member of a group (gender or ethnicity) could be a source of self-esteem and pride. Given the majority status of white people in the United States and the presence of white privilege in U.S. history, being white could positively impact one’s CSEs. Also, given the traditionally dominant status of males and historical privilege in the United States, being male could also relate.

Accordingly, we offer the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Males will have higher CSE levels than females.

Hypothesis 2: White participants will have higher CSEs than non-whites.

Social norms in countries with a strong work ethic encourage people to work; being employed has been found to correlate with lifestyle satisfaction and happiness (Winkelmann, 2014). People who are employed may further have a higher locus of control (a key component of CSE) as they are taking responsibility and accountability for themselves. In a study of highly educated Israelis, Shamir (1986) did not identify a relationship between employment status and self-esteem. In contrast, Waters and Moore (2002) found the self-esteem of continuously unemployed participants in Australia to be lower than their re-employed or continuously employed counterparts (Waters & Moore, 2002). Additionally, prior studies have found that CSEs correlate to career success (Judge & Hurst, 2008), work engagement (Rich et al., 2010), and job satisfaction (Stumpp et al., 2010).

Another component of the core self-evaluation construct is low neuroticism (anxiety, worrying). Higher levels of neuroticism correspond to lower levels of work engagement (Furnham et al., 2023). Prior research in Sweden has found lower levels of anxiety among the employed versus their unemployed counterparts (Hiswåls et al., 2017). This finding is intuitive since the unemployed may be less likely to be able to pay their basic expenses.

Taken together, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Employment status will correspond positively with CSEs.

Perceived competence is an important factor in an individual’s CSEs. Within a university setting, we would expect students who have earned high GPAs to perceive themselves as more competent with higher capabilities than students who have earned lower GPAs. Additionally, students with higher GPAs may also expect greater job opportunities upon completion of college since employers can use GPAs as proxies for one’s work ethic (Indeed.com, 2022) which would also influence their CSEs. Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 4: GPA will correspond positively with CSEs.

Self-Enhancement

In numerous studies, Schwartz (2012) has identified ten motivationally distinct values that are recognized across all cultures, which people draw from to inform their behaviors and actions. Schwartz (2012) identified six characteristics of values: (1) they are beliefs; (2) they refer to desirable goals; (3) they transcend specific situations and actions; (4) they serve as standards or criteria; (5) they are ordered by importance; and (6) the relative importance of multiple values guides actions. The values are as follows: benevolence, universalism, self-direction, stimulation, hedonism, power, achievement, security, tradition, and conformity. From these values, four higher-order domains emerge: self-transcendence (benevolence and universalism), self-enhancement (power and achievement), openness to change (self-direction, stimulation, and hedonism), and conservation (security, tradition, and conformity) (Schwartz, 2012). Individuals with a high self-enhancement (SE) motivation behave in ways that increase social superiority and self-esteem (Schwartz, 2012). SE leads to a focus on oneself versus focusing on others (putting their own needs above the needs of others) along with a desire to protect oneself by actively controlling threats or meeting social standards, which reinforces perceptions of competence and lowers anxiety (Schwartz, 2012).

Personality traits are partially heritable (Ilies et al., 2006), while values are products of one’s culture and environment (Hofstede, 2001). Roccas, Sagiv, Schwartz, and Knafo (2002) applied Bem’s (1972) self-perception theory to proffer that personality traits can have an impact in shaping one’s values; as people see their own behavior, they consider the values that could have caused that behavior. Previous research supports self-perception theory showing that narcissism is associated with higher levels of SE values (Anello et al., 2019; Campbell et al., 2000). SE values are also associated with higher levels of self-deceptive enhancement. In other words, individuals give positively-biased representations of themselves to protect their self-esteem (Danioni & Barni, 2021).

Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 5: Self-enhancement values will correspond positively with CSEs.

Psychological Entitlement (PE)

Psychological entitlement (PE) is “a stable (i.e., trait-like) and global tendency toward favorable self-perceptions and reward expectations that exists even when there is little justification for such beliefs” (see definitions from Campbell et al., 2004; Naumann et al., 2002). Similar to CSE, PE involves perceptions of oneself but unlike CSE, individuals with high PE have a positively biased view of themselves and what they deserve. Similar to CSE, PE tends to be more of an individual difference that impacts behaviors across situations (Campbell et al., 2004). Higher levels of PE correlate with higher levels of narcissism, which is in direct contrast to CSE where higher CSE levels are related to lower narcissism levels.

CSE and PE affect both behavior and perceptions in the workplace in contrasting ways. CSE tends to be associated with positive work behavior and attitudes, while PE is correlated with a variety of negative personal and work outcomes such as greediness (Campbell et al., 2004), moral disengagement at work (Ogunfowora et al., 2021), self-serving actions, malicious intentions, lower scores on the multidimensional ethics scale (Thomason & Brownlee, 2018), and psychological distress (Grubbs & Exline, 2016). People with lower levels of PE would also be less likely to work for a socially responsible workplace if it meant they would be paid less (Thomason et al., 2015). Prior studies have also found that more entitled students felt it was more important to earn top grades and the more important top grades were, the more students felt their parents expected them to earn top grades (Ritzer & Sleigh, 2019).

PE can correspond to some positive outcomes too. Entitlement may help when workers are dealing with work-family conflicts as less entitled employees are most negatively impacted by work-family conflicts (Laird et al., 2021). Laird and colleagues (2021) posit that PE provides the self-confidence and resources needed to weather work-family conflicts. Entitled workers may also respond favorability to working conditions in which accountability is high (Laird et al., 2015).

Academic entitlement (AE) is a related, but distinct construct (Chowning & Campbell, 2009; Kopp et al., 2011) that refers to the belief that one should receive high grades despite modest efforts (Greenberger et al., 2008). People with high levels of AE engage in greater academic dishonesty and tend to have exploitive attitudes towards others and demanding attitudes towards their teachers (Greenberger et al., 2008). Wasieleski et al. (2014) included academic narcissism and academic outcomes in their AE scale, finding that academic narcissism related negatively to GPA, while academic outcomes were not significantly related. PE items from the Campbell et al. (2004) scale include related items that reflect narcissism and deservingness. While high PE individuals may realize that earning high grades is important (e.g., Ritzer & Sleigh, 2019), they may feel that the effort they put in is deserving of high grades, despite any shortcomings in inputs. Given the close relationship between the constructs of psychological entitlement (PE) and academic entitlement and the counterproductive components of PE, we propose a negative relationship between PE and self-reported GPAs.

Hypothesis 6: GPAs will correspond negatively to PE.

Hypothesis 7: SE will correspond positively to PE.

Hypothesis 8: Employment status will correspond positively with PE.

Method

We surveyed 189 university undergraduate students enrolled in 300-level business management courses at a medium-sized, sectarian private university in the southeastern United States. Students were asked to voluntarily complete the first phase of the surveys after signing an informed consent form from the Institutional Review Board. To reduce the potential for self-report bias, we also asked them to ask a close friend, significant other, or relative to complete the 21-item Portrait Values Survey about the student respondents. We randomly re-ordered the survey constructs in the survey for some of the respondents to reduce any ordering bias.

Core Self-Evaluation Scale

We used the 12-item Core Self-Evaluation Scale by Judge, Erez, Bono, and Thoresen (2003), which has been validated in multiple studies and has demonstrated psychometric reliability (Ock et al., 2021). The scale is anchored by a 5-point Likert scale with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. A sample item is “When I try, I generally succeed.” After reversing the scores of items 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12, we calculated the mean score for the overall core self-evaluations scale.

Psychological Entitlement Scale

We used the 9-item Psychological Entitlement Scale by Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman (2004) anchored by a 7-point Likert scale of 1 = strong disagreement and 7 = strong agreement. A sample item on this scale is “If I were on the Titanic, I would deserve to be on the first lifeboat!” After reversing the score of item 5, we calculated the mean score for the overall psychological entitlement scale.

Self-Enhancement

We used the 21-item Portrait Values Survey from the European Social Survey website, which assesses four domains from ten values (Schwartz, n.d.). We asked our participants to give this survey to a significant other, close friend, or relative and asked that person to complete the survey about the original respondent. This scale is anchored by a 6-point Likert scale anchored by 1 = not like him/her at all and 6 = very much like him/her. We calculated the mean score of the two items representing power (2,17) and achievement (4,13) for the self-enhancement score. A sample item for this scale is “It’s very important to him/her to show his/her abilities. He/she wants people to admire what he/she does.”

Demographic Variables

We collected the age, gender, ethnicity, self-reported GPA, university level, political affiliation, marital status, dependents, years of full-time work experience, years of supervisory experience, whether the student is currently employed, and (if so) the number of hours the student averages working each week. Due to small numbers of students who identified with an ethnicity other than white, we collapsed the seven categories into dummy variables (1, 0) of “white” and “non-white.” 143 students identified themselves as white and 44 were non-white. 85 identified as male, 102 identified as female, 1 identified as nonbinary, while 2 did not disclose their gender. Student ages ranged between 18 and 41 with a mean of 21.14 and a standard deviation of 2.39. The mean self-reported GPA for 81 males was 3.21, SD=.39, while for 104 females was 3.42, SD=.39. These differences were significant (p<.001).

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the study variables, along with Cronbach’s alpha for reliability assessments.

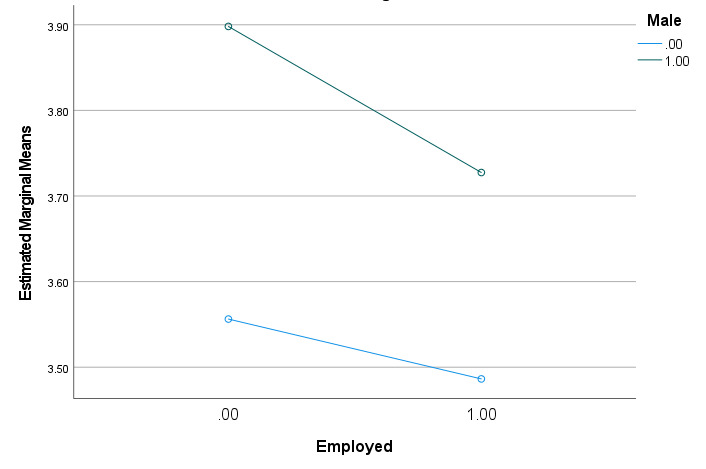

To test the first four hypotheses that males and white students will have higher core self-evaluations than females and non-whites, employed students will have higher core self-evaluations than unemployed students, and CSEs will correspond positively to GPAs, we initially inspected mean differences in the CSE scale between males and females. The mean CSE for 85 males was 3.81, SD .51, while the mean for 101 females was 3.51, SD .50. T tests indicated significant differences at the p<.001 level. The mean for 142 whites was 3.69, SD .50, while the mean for non-whites was 3.53, SD .57. These differences were not significant, indicating a lack of support for hypothesis 2. The mean for 101 employed students was 3.57, SD .53, while the mean for the 83 unemployed students was 3.74, SD .50. T tests indicated significant differences at the p<.03 level.

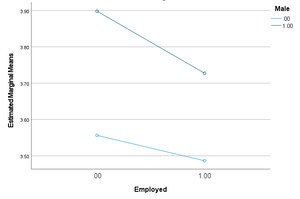

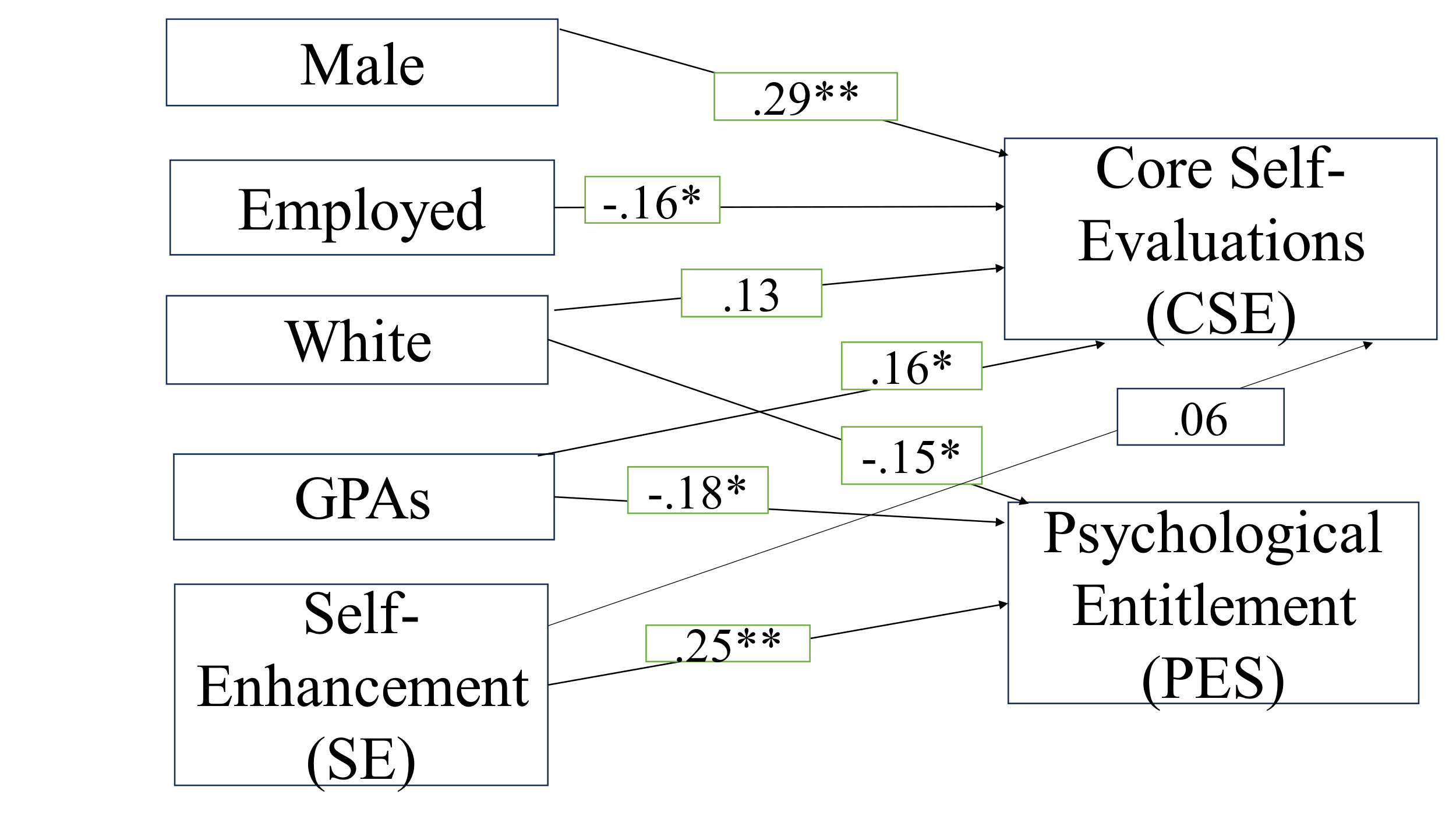

We next conducted a hierarchical multiple regression analysis with the dependent variable of CSEs and the independent dummy gender (male/female 1,0) in the first step. In the second step, we entered the dummy variable for employment status (employed/unemployed 1,0), self-reported GPAs, and others-reported SE. In this analysis, we checked for outliers beyond 3 standard deviations and did not identify any. Results indicated significance for both equations. In the second equation, the F score (F=7.74 p<.001, 175, 4 degrees of freedom) was significant. The R2 for the first model was .11 (p<.001) and the R2 change was .04 (p<.05), indicating the independent variables account for 15 percent of the variance in core self-evaluations. While our results supported our first hypothesis, surprisingly, the results between employment and core self-evaluations suggest a negative relationship. In other words, students who were not employed while in college had higher core self-evaluations than their working counterparts. Table 2 reports the results.

Due to relatively small sample sizes, we next applied a bootstrap analysis with simple sampling using a sample of 5,000 and a 95 percent bias-corrected confidence interval. Results indicated further support for the relationships between CSEs and being a male with a confidence interval between .205 and .500 (standard error .08; p <.001) and being employed with a confidence interval between -.307 and -.003 (p<.05). Since the confidence intervals in both variables did not include zero, we can assume the regression parameter is significant. GPA and SE were not significant in this analysis.

We next entered CSEs into a 2 (employed vs. not employed) by 2 (male vs. female) ANOVA through a univariate general linear model using SPSS and a profile plot to determine whether interactions were present. The dependent variable was CSEs and the fixed factors were the dummy categorical variables for employment and gender. We checked our data to ensure its fit with the assumptions of a normal distribution for the dependent continuous variable, independence of observations, Levene’s test of the homogeneity of variances, and outliers. The interaction between gender and employment was not significant. We next assessed relationships using Crosstabs between the nominal variables (gender, employed) in the column and the interval variable in the row, to obtain the eta directional measure, which is the crosstabs value of the dependent variable of CSE. The eta value for the dependent CSE x male was .29 while the CSE x employed was .16. Squaring the eta (η) value gives us the proportion of variance in CSE that is explained by gender (male/female 1,0) and being employed/unemployed (1,0). These findings indicate we can reject the null hypotheses that there are no relationships between gender, being employed, and CSEs.

To test the hypotheses that higher GPAs, higher levels of SE, and being employed would correspond to higher levels of PE, we conducted a hierarchical multiple regression with the control dummy variables representing gender and ethnicity in the first step and the employment dummy variable, GPA, and SE in the second step, which we regressed onto psychological entitlement. We included ethnicity as a control variable since we found a significant (p<05) relationship between ethnicity and PE. Results provided partial support. While the first step of the model was not significant, the additional variables in the second step were significant. In this step, the overall model was significant (F=4.76, p<.001, df 170,5) and the R2 of .12 was significant at the p<.001 level. As hypothesized, we found a positive relationship between SE and PE and a negative relationship between GPA and PE. In other words, students with lower GPAs had higher levels of PE. We further found a relationship between ethnicity and PE, which we had not hypothesized. We did not find a relationship between PE and being employed.

The means for PE between whites (mean = 3.50, SD .97, n=143) and non-whites (mean = 3.84, SD .89, n=44) were significant (2-tailed test) p<.05. Mean differences between ethnicities on SE were not significant. We also ran a simple sampling bootstrap analysis with 5,000 bias-corrected samples to gain further perspectives on generalizability since our sample sizes were relatively small. Results indicated significant relationships between PE and ethnicity with a 95 percent confidence interval between -.67 and -.05 (standard error .16, p<.02), GPA with a 95 percent confidence interval between -.73 and -.08 (standard error .17, p<.02), and SE with a 95 percent confidence interval between .12 and .42 (standard error .07, p<.001). Each of these confidence intervals did not include zero, indicating significance.

Discussion

As noted at the outset, people with high CSEs enjoy a variety of positive work and life satisfaction outcomes. They further enjoy long-term benefits, with a cumulative advantage in their careers, greater career success, higher pay, better health, and more educational attainment (Judge & Hurst, 2008). CSEs also correspond to fewer financial strains and higher income over a longitudinal period (Judge et al., 2009). The results in our dataset, which are supported through the boot strapping methodology, provide some support for the hypothesis that males have higher CSEs. CSE levels for males are higher than females even though the females’ GPAs in our sample were higher than male GPAs. While we hypothesized that employment would positively relate to CSEs, our results suggest a negative relationship exists for our sample of U.S. undergraduate business students in a private university.

Implications

Small business leaders may use these types of personality assessments to select job candidates who are the right fit for their missions, visions, and goals. Some may use CSEs since high CSEs are related to a variety of positive work outcomes. CSEs also have been shown to have incremental validity over the Five Factor Model of Personality, narcissism, self-esteem, and the Protestant Work Ethic in predicting job performance (e.g., Judge et al., 2003; Rode et al., 2012). Our findings suggest that small business leaders may want to exercise caution if using CSEs when selecting employees since CSEs appear to adversely impact females. Companies using CSEs could inadvertently favor males over females, leading to potential claims of workplace discrimination. Our results are especially concerning given our finding that males had higher CSEs even when their actual performance, as measured by GPA, was lower than females. Prior studies that have focused on correlates of work engagement have also found sex differences in neuroticism and intelligence (Abraham et al., 2023), so caution in using these variables when making hiring decisions may be warranted. Small business leaders who use personality assessments may want to assess a wide variety of personality characteristics in addition to assessing candidates’ cognitive or ethical characteristics to maximize the validity of their decisions.

We also found support through bootstrapping for our hypothesis that people with high levels of SE (as rated by others) have higher levels of PE, while we found that self-reported GPAs and PE negatively relate. These findings provide support for both the pros and cons of PE. On one hand, higher SE (power and achievement values) can be beneficial to people who value a strong work ethic and influence on others. On the other hand, those with lower GPAs may believe they are entitled to outcomes that they haven’t earned.

Our findings provide some support for social identity theory as males who have historically had privileges in the United States culture may feel more confident about themselves than females. Undergraduate males appear to have higher self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability than their female counterparts. Along these same theoretical lines, we expected white vs. non-white differences in CSEs. While other researchers have found this relationship (Griggs & Crawford, 2019), we found a positive relationship (.13, p = .07), that did not rise to the level of significance. Future studies may consider replications in countries with different demographic characteristics to determine whether historically favored groups enjoy higher CSEs than their counterparts in those locations as well. In a famous Ted Talk entitled “Why we have too few women leaders,” Sheryl Sandberg (former chief operating officer of Facebook) shared a story from her past in college (Sandberg, 2010). Sandberg, her brother (“smart guy, but a water-polo-playing pre-med”) and another female took a course entitled “European Intellectual History” together. She and her girlfriend attended most of the lectures while her brother only attended a couple. To prepare for the exam, Sandberg read the twelve books assigned in English, her girlfriend read them in English, the original Greek, and the original Latin, while her brother only read one. A couple of days before the exam, he hired a tutor. Just after taking their exams, Sandberg and her girlfriend lamented their performance, while her brother beamed that he expected a top grade in the class. This story helped to fuel her call to action for women who need to stop downplaying their accomplishments and abilities. Her call is relevant in the present context as women in our study reported higher average GPAs and lower core self-evaluations. Given the relationships between core self-evaluations and numerous beneficial work and personal outcomes noted at the outset, women who report lower CSEs may want to consider ways to increase their self-esteem, self-confidence, locus of control, and emotional stability.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Our findings suggest that university students who are unemployed and/or males have greater levels of CSEs. While we did not propose that being unemployed would be associated with higher CSE levels, the results suggest the characteristics of our sample need to be considered: business students in a private university. Students come from families of varying levels of socioeconomic status where some may not need to work to support themselves while in school. Future studies should consider family income or wealth as moderators between the relationship between CSEs and employment status especially when university students are used as the sample. It is likely that those who come from wealthier families and who do not need to work to support themselves may evaluate themselves more favorably. We further found an un-hypothesized relationship between ethnicity and PE with non-whites having higher levels than their white counterparts. These findings may be due to the relatively small proportion of nonwhite students in the sample (44 nonwhite and 143 white) and the diversity within the population of nonwhite students. For example, 19 white and 8 nonwhite students were not citizens of the United States and the sample contained 16 Hispanics, 11 Asian/Pacific islanders, 7 “others,” 6 African Americans, and 4 Arabs. Rather than capitalize on chance findings, we encourage future studies to use larger samples within these categories to analyze these relationships.

We further acknowledge that while we included self-reported GPAs, students may not always accurately recall their GPAs. They may further report higher GPAs than they have actually attained. In addition, the relationship between their GPAs and their CSEs may be correlational, not causal. GPAs could influence CSEs and CSEs may result in higher GPAs. As personality traits are partially heritable (Ilies et al., 2006), it may be likely that such traits precede outcomes such as GPAs, so future research may want to incorporate longitudinal models to determine causality.

Conclusion

While we hypothesized that male students, employed students, and students with higher self-reported GPAs would have higher core self-evaluations than their counterparts, our findings only offered partial support. Surprisingly, unemployed students reported higher CSEs. Students with lower GPAs also reported higher levels of psychological entitlement. Given many aforementioned studies showing positive work and life outcomes for people with higher CSEs and negative behaviors and attitudes for people with higher PEs, we urge researchers to examine these relationships further. Why would females and employed students have lower CSEs than their counterparts? Which individual, familial, organizational, or societal factors could have contributed to these relationships? In Sheryl Sandberg’s Ted Talk, she urged women to be confident and to lean in and go after higher level organizational positions. We concur. Otherwise, women may be missing out on some important opportunities and achievements.